|

At the end of winter, sap starts flowing from tree roots back up the trunk. This sap contains the vital nutrients that trees need to survive and thrive. We visited Waubonsie State Park in Fremont County on a warm day in early March to practice tapping trees with Park Manager Matt Moles. Always check with property managers before tapping trees on public lands. We received approval to do this for educational purposes. The process is a lot simpler than many people might expect. Basically you find a tree you want to tap and drill a hole that will fit the size of your spile. The hole should be at a slight upward angle to help the sap drip down the spile. If the sap is flowing, you will likely see it dripping out already. We used inexpensive plastic spiles found online but traditionally the spiles were made of metal. Next, attach a tube to the spile and tap the spile into the drilled hole so that it fits tightly and will not fall out of the tree. Measure beforehand to ensure the tubing will fit on your spiles. Below you can see the sap flowing from the spile into the tube. Put the other (bottom) end of the tube into some kind of container like a bucket placed on the ground. You could also hang the bucket on the tree and eliminate the need for the tubing. Make sure to wash the bucket, tubing, and spiles before and after each use, and don't use a bucket that has stored any toxic substances. Depending on the tree, the weather, and other factors, the sap my drip quite slowly or flow fairly rapidly like this one: It's best to cover the bucket to prevent insects, dust, and other debris from settling into the sap. Check the bucket regularly to make sure it doesn't overflow.

Now you've done the easy part! Turning the sap into syrup requires boiling it down until the water evaporates, leaving mostly sugar. Maples generally have higher sugar content than most other trees, which means it takes less boiling to get more syrup. Still, many other species can be tapped. Even with maples, a rough estimate is about 40 gallons of sap boils down to one gallon of maple syrup. For other species, the difference is even greater. If you don't have the right equipment to boil down that much sap, start small and try it out on your stovetop or over an outdoor fire. You can also skip the boiling process completely and drink the sap alone or with other beverages like coffee or tea. Sap, or maple water, as it's been branded, is marketed as a healthy alternative to sugary drinks. It has a slightly sweet taste and includes some nutrients and electrolytes. For more details on tapping trees, check out this recent blog post from Perennial Homestead.

0 Comments

National Bison Day, held annually the first Saturday of November, is a "commemoration of the ecological, cultural, historical and economic contribution of a national icon, the American bison." According to the National Bison Association: "The bison, North America’s largest land mammal, have an important role in America’s history, culture and economy. Before being nearly wiped from existence by westward expansion, bison roamed across most of North America. The species is acknowledged as the first American conservation success story, having been brought back from the brink of extinction by a concerted effort of ranchers, conservationists and politicians to save the species in the early 20th century. In 1907, President Teddy Roosevelt and the American Bison Society began this effort by shipping 15 animals by train from the Bronx Zoo to Oklahoma’s Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge. Many Native American tribes revere bison as a sacred and spiritual symbol of their heritage and maintain private bison herds on tribal lands throughout the West. Bison now exist in all 50 states in public and private herds, providing recreation opportunities for wildlife viewers in zoos, refuges and parks and sustaining the multimillion dollar bison ranching and production business." While National Parks in the mountain west are typically thought of, bison were once abundant across Iowa. No wild populations remain, but several public and private landowners in the state have bison today. One great way to celebrate National Bison Day is to visit one of several places in western Iowa with public viewing of bison. Botna Bend Park This park is owned and managed by Pottawattamie Conservation and is located in the town of Hancock in eastern Pottawattamie County. It is located within the the Loess Hills Missouri River Region and along the West Nish Water Trail. The park includes bison and elk herds that can be easily viewed from the road. The park has a $3 entrance fee unless you have a Pottawattamie county parks annual pass. Botna Bend even has two white bison, which are extremely rare: Broken Kettle Grassland The Nature Conservancy in Iowa owns the largest remnant prairie in the state in Plymouth County along the northern end of the Loess Hills National Scenic Byway, and includes a herd of bison. Because they have a relatively large area to roam, you may not be able to get close. But drive Butcher Road and you may see them in the distance. Prairie Heritage Center O'Brien County Conservation Board's Prairie Heritage Center, along Glacial Trail Scenic Byway, has a small herd of bison. Swan Lake State Park Located in Carroll County, this park is managed by Carroll County Conservation Board and has a small bison herd. Whiterock Conservancy This 5,500-acre land trust is a short drive from Western Skies Scenic Byway in Guthrie County. Whiterock is open to public visitation and includes dozens of miles of hiking, mountain biking, equestrian trails, camping, paddling, fishing, and much more. Golden Hills partnered with Raygun to create a WanderLoess bison shirt to support our Loess Hills conservation work.

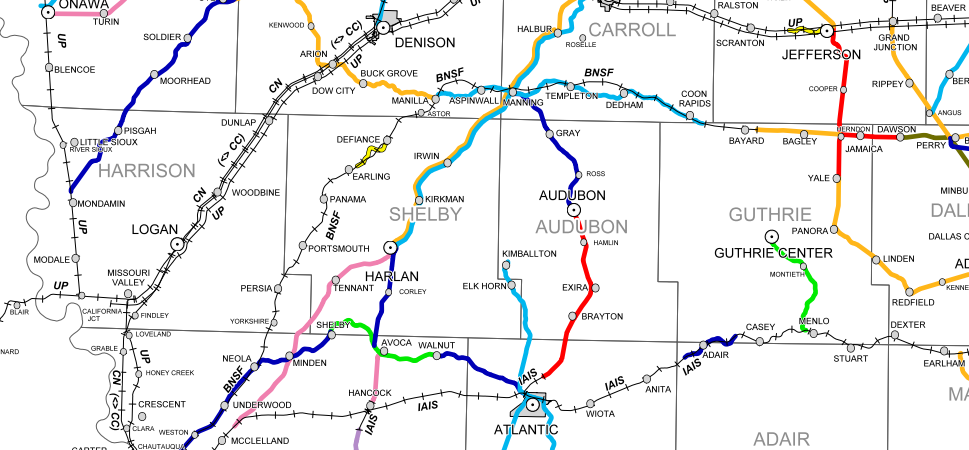

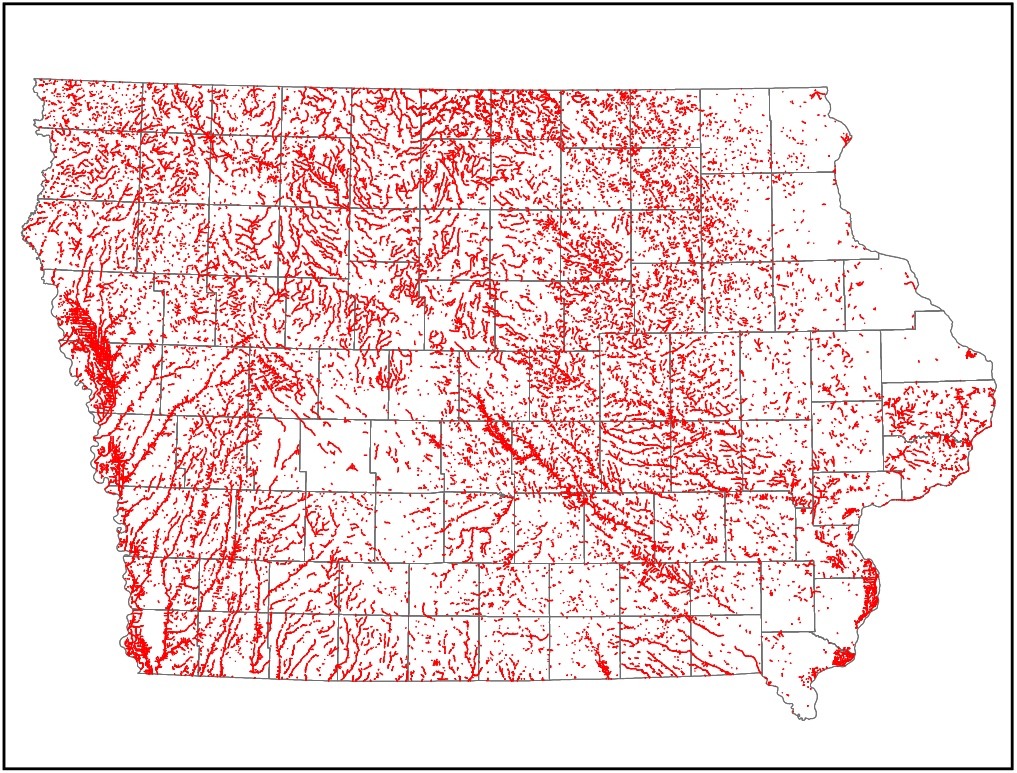

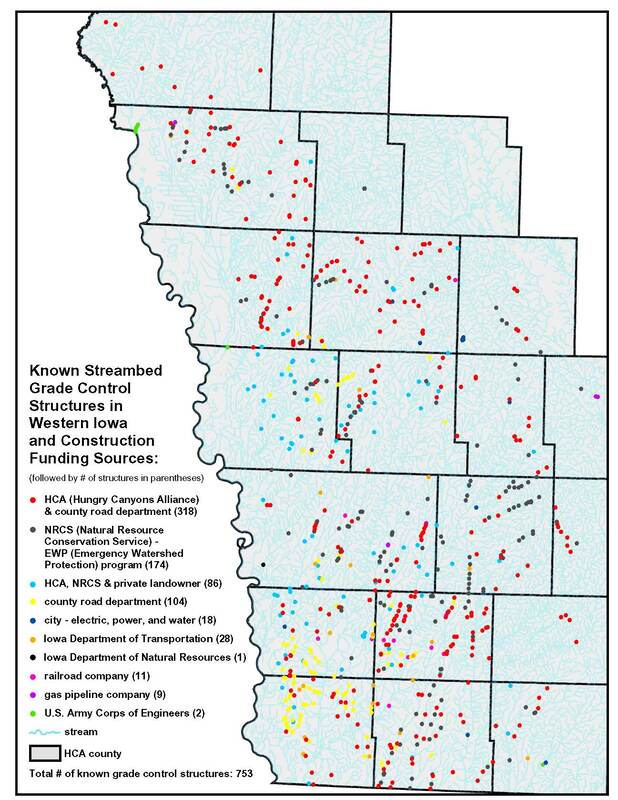

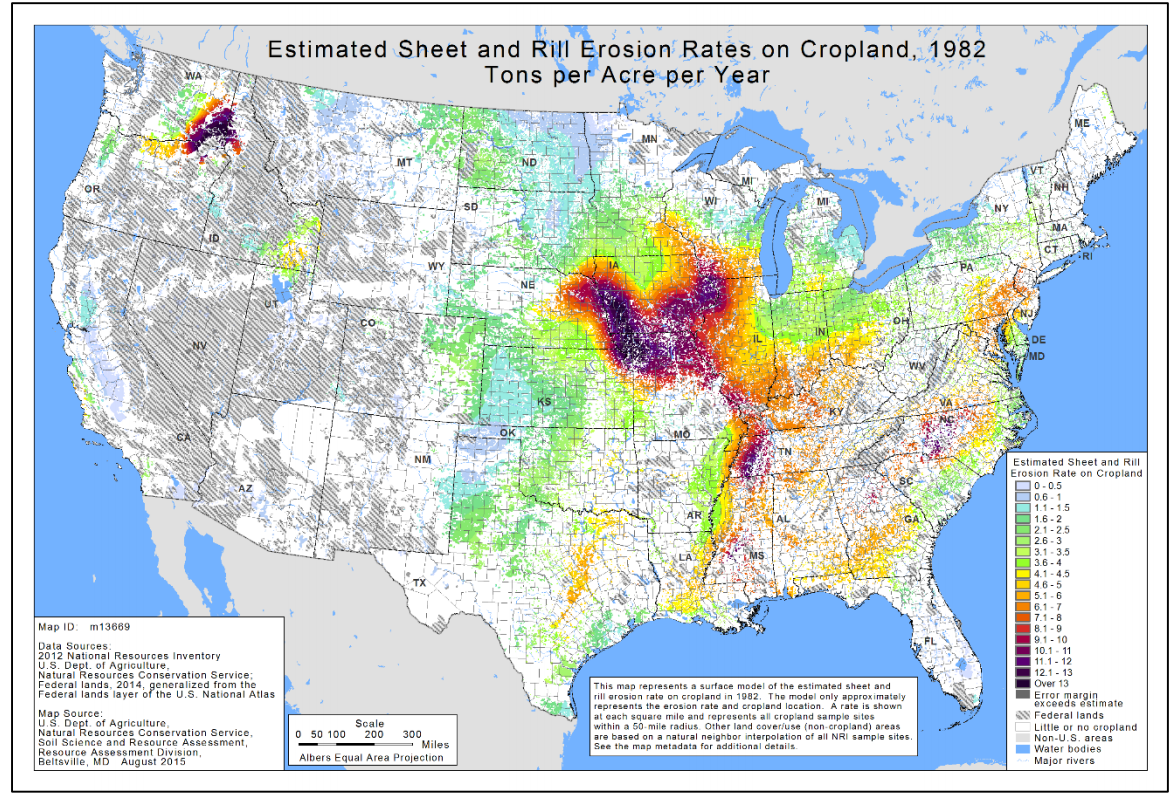

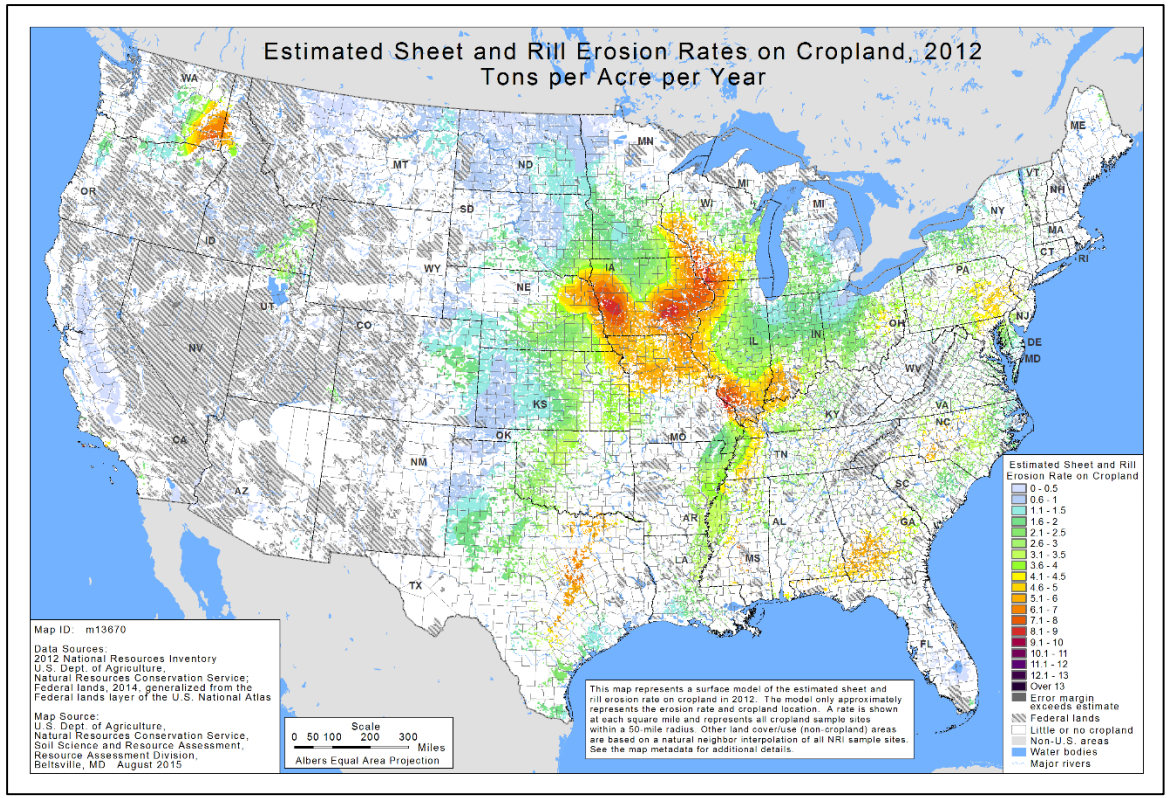

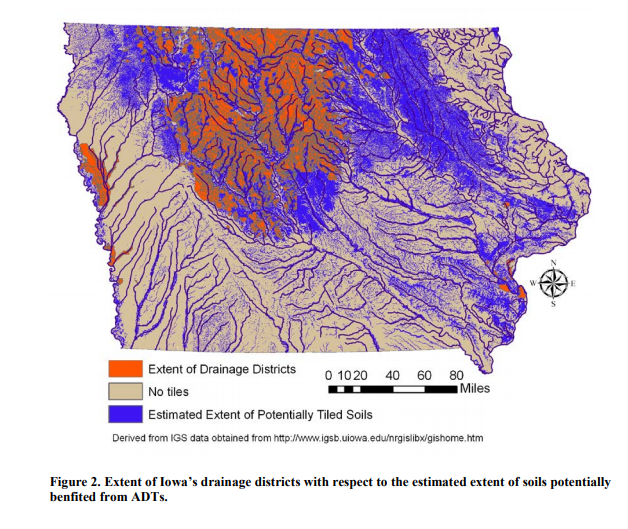

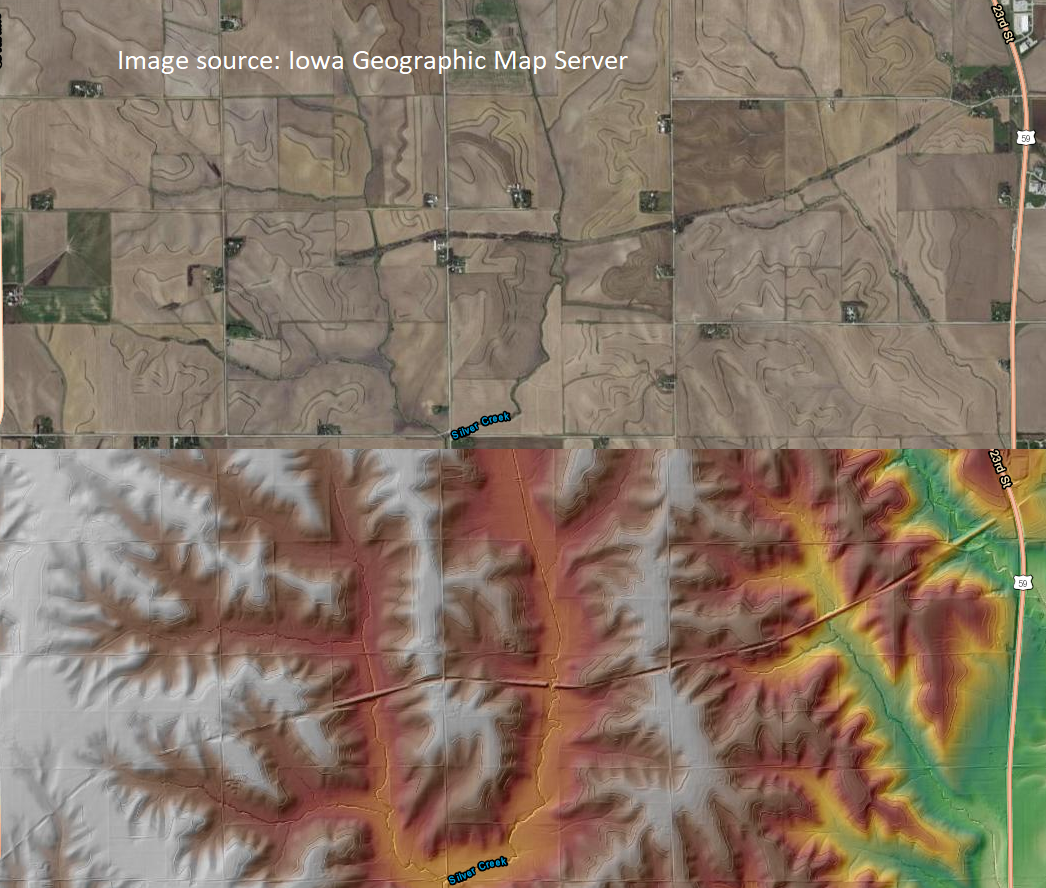

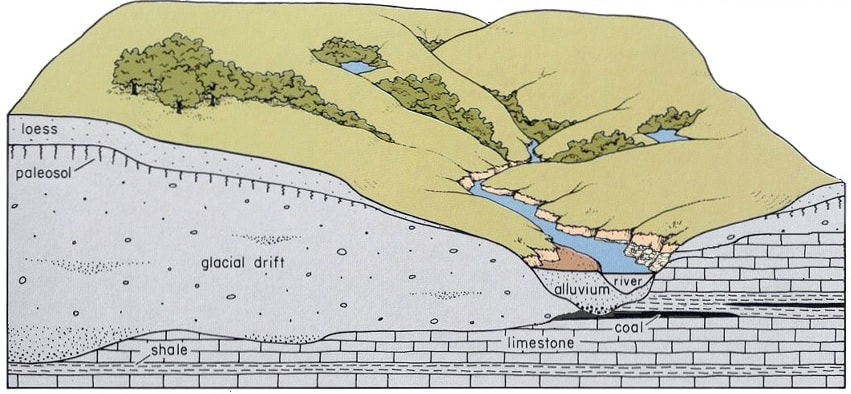

In a previous post about Western Skies Scenic Byway, we discussed how wind and water shaped the landscape of western Iowa. In addition to natural forces, people have also helped shape the modern landscape. Humans have inhabited the land that is western Iowa for thousands of years, impacting the landscape since the beginning. Indigenous people cultivated crops, built homes, and started regular fires. After European colonization beginning in the late 19th century, the land changed much more dramatically and rapidly. The contemporary landscape of western Iowa would be unrecognizable compared to the vast prairies and wetlands that covered the state prior to colonization. Iowa is the most altered of all 50 states, with the least amount of "wild" or "natural" places. "The state of Iowa has lost 99.9% of its prairies, 98% percent of its wetlands, 80% of its woodlands, 50% percent of its topsoils, and more than 100 species of wildlife since settlement in the early 1800’s. There has been a significant deterioration in the quality of Iowa’s surface waters and groundwaters." (Source: Iowa Code, Section 455A.15 Legislative Findings). The region has some of the best cropland in the world, and prairies and wetlands were converted to rowcrops over only a couple generations. Many of the steeper slopes were converted to non-native pastures. With this vegetation and land use change, the entire ecosystem changed from some of the most biodiversity on the planet to among the least. On top of the vegetative change, nearly all the rivers and creeks in western Iowa were channelized in the 20th Century. Straightening streams shortened their length, which increased the slope and caused the waterways to cut downwards into the deep, highly erodible loess soils. Most streams in the region have severe to extreme bank erosion and are carved 10 to 20 feet (or more) into the surrounding land. The increased stream slope also led to widespread gully erosion, with small waterfalls called knickpoints on many streams. The drastic elevation changes have required streambed grade control structures like spillways and dams to help protect roads, bridges, utilities and other infrastructure. Due to their silty nature, the deep loess soils are home to the worst soil erosion on the continent. In fact, "loess" is a German word for "loose" and is colloquially called "sugarclay" due its erosiveness. The maps below show rill and sheet erosion in the continental U.S. in 2012 and 1982. While erosion has been reduced from more than 12 tons per acre to 6-8 tons per acre, this is still a concerning erosion rate. Learn about different types of soil erosion here. Fortunately, agricultural conservation practices, especially terraces and water and sediment control basins, have reduced erosion. Planting rowcrops on contour instead of vertically on slopes also helps to slow erosion rates. These practices are nearly ubiquitous on western Iowa's croplands, further shaping the landscape. The earthen berms reduce rill and sheet erosion and runoff. Prior to colonization and subsequent stream channelization, the prairie streams meandered across their valleys with crystal-clear water, as described in some early pioneer accounts. Today the sheet, rill, gully and streambank erosion makes the streams run a muddy brown color. New evidence has shown that phosphorous levels in streams are likely impacted significantly by streambank erosion, as "legacy" nutrients get stored in the soil and enter waterways when riverbanks erode. Some of the poorly-drained areas, especially on the Des Moines lobe in northeastern Guthrie County and some of the larger river valleys like the Missouri in Harrison County, were tiled to convey water off the land and improve agricultural opportunities. Tiling can carry nutrients, sediment, and pollutants into drainage ditches and streams, further decreasing water quality. Tiling is usually invisible above ground, but you may see the end of tile lines going into drainage districts or streams. Learn more about tiling and terracing here. Besides agricultural development, humans have built residential, industrial, commercial, and other infrastructure that shapes the land. Most of the communities in the region were founded along rail lines, which were some of the earliest transportation routes before many roads were built.  Source: Iowa DOT (https://iowadot.gov/iowarail/IOWA-FREIGHT-RAIL/RAILROAD-MAPS) Source: Iowa DOT (https://iowadot.gov/iowarail/IOWA-FREIGHT-RAIL/RAILROAD-MAPS) Most railroads in this corridor have been abandoned and are no longer active. Some have been replaced by recreational trails like the T-Bone Trail through Audubon County and the Raccoon River Valley Trail in Guthrie County. Many others were removed and have been farmed for decades, with no trace remaining. In some cases, the remnants are visible from satellite imagery and LIDAR, like this area just southwest of Harlan in Shelby County. Many settlements that began before railroad construction eventually withered into ghost towns. In some cases, a few houses remain, but often there are no visible signs of these ghost towns on the landscape. The highway and road system also greatly contributed to the region's altered landscape and hydrology. For the most part, roadways are built up several feet from the surrounding landscape similar to railroads, and cut into the tops of the hills to reduce slopes. Unlike the railroads, which often followed the path of least resistance, the road system was set up on orthogonal grid system oriented along the cardinal directions, regardless of terrain. Some exceptions to the grid exist, especially in the hilliest parts of Harrison and Guthrie counties. Since the grid does not follow topographic or hydrologic boundaries, the construction of the road system in some cases altered watershed boundaries. Ditches on either side of the roads funnel water into the nearest stream, increasing flash flooding and nutrient runoff. Next time you drive Western Skies Scenic Byway, try to spot how the land has been sculpted by human development, in addition to natural processes like wind and water.

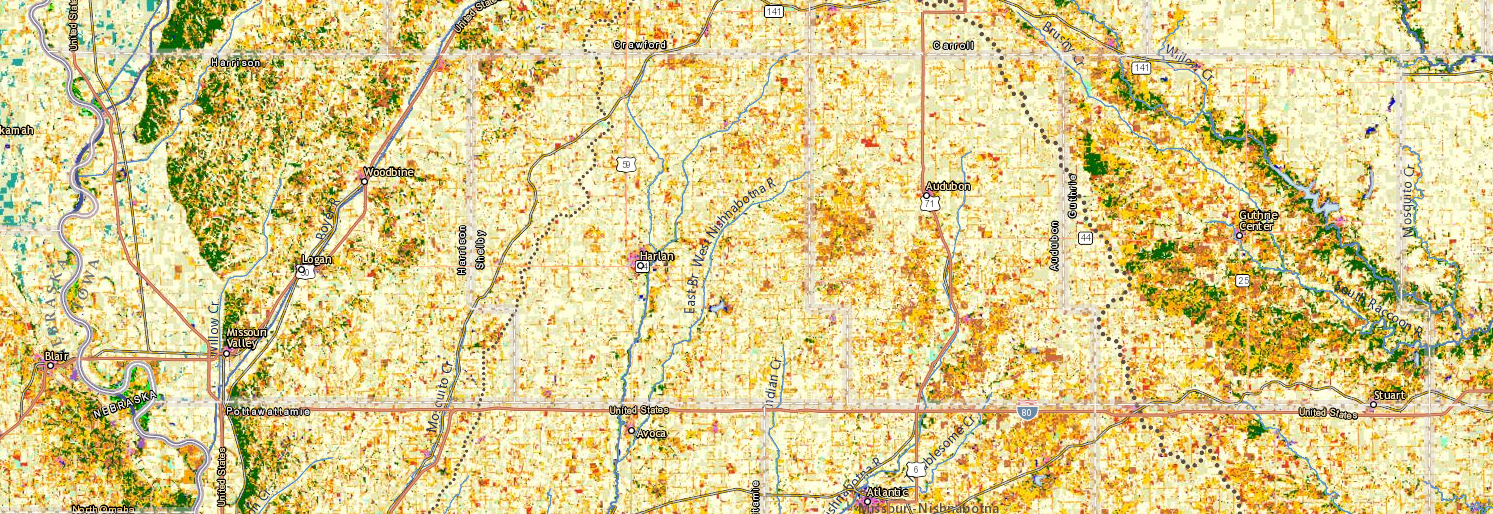

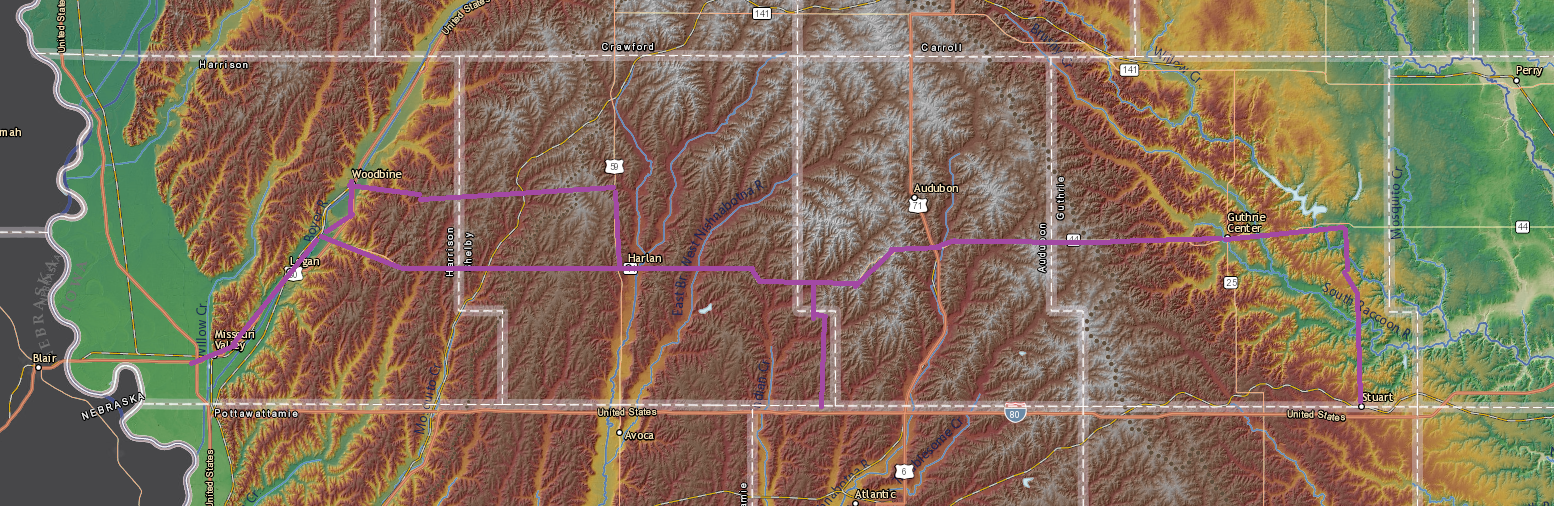

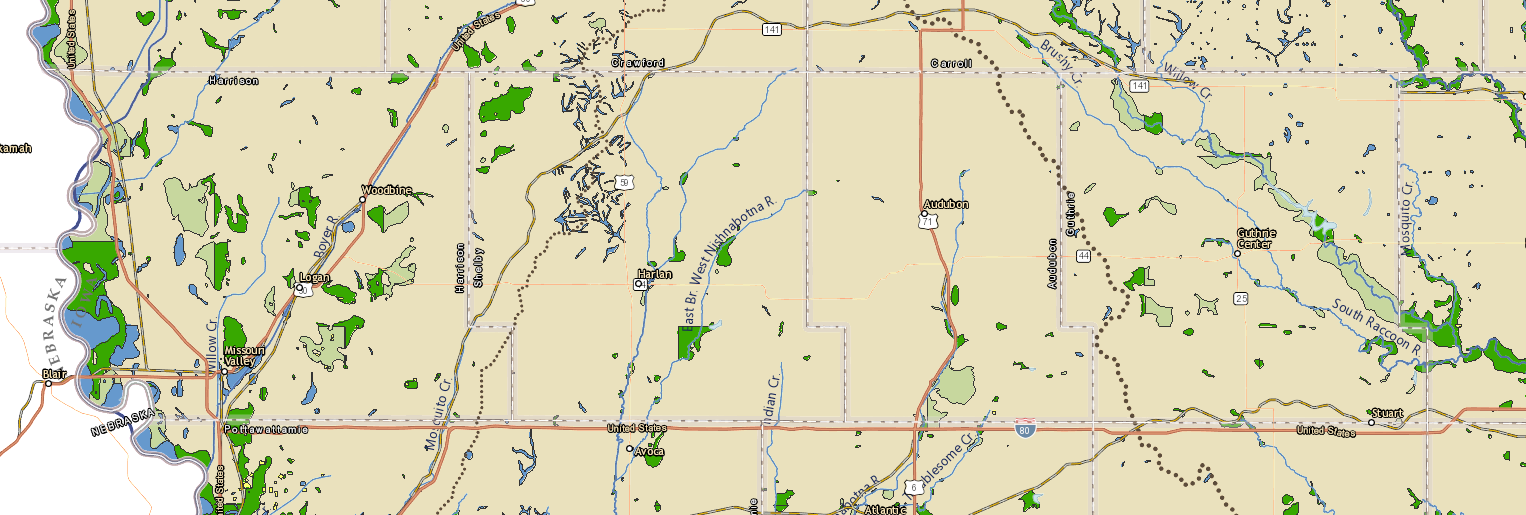

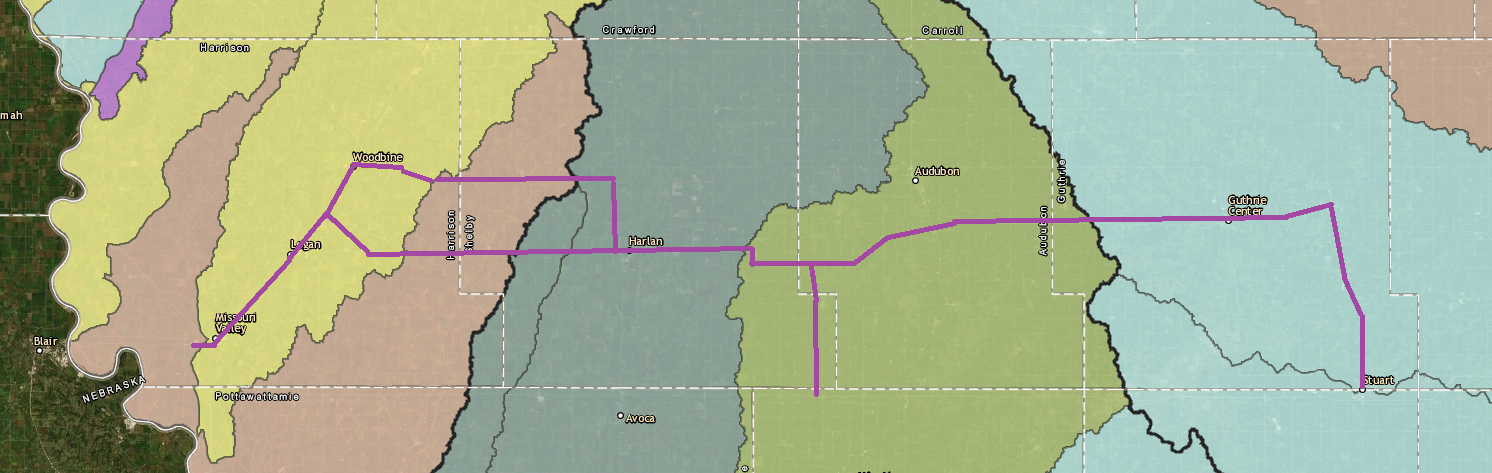

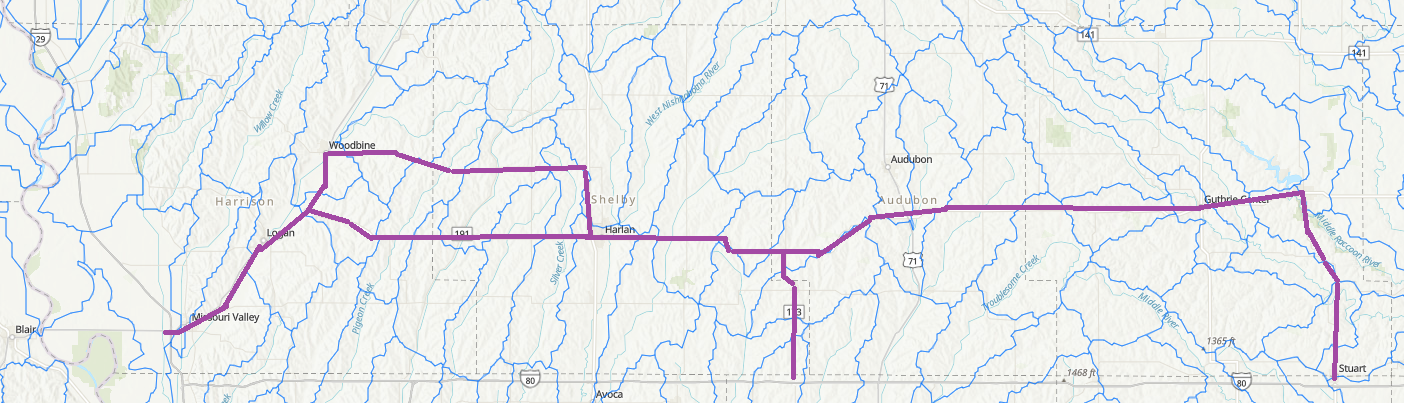

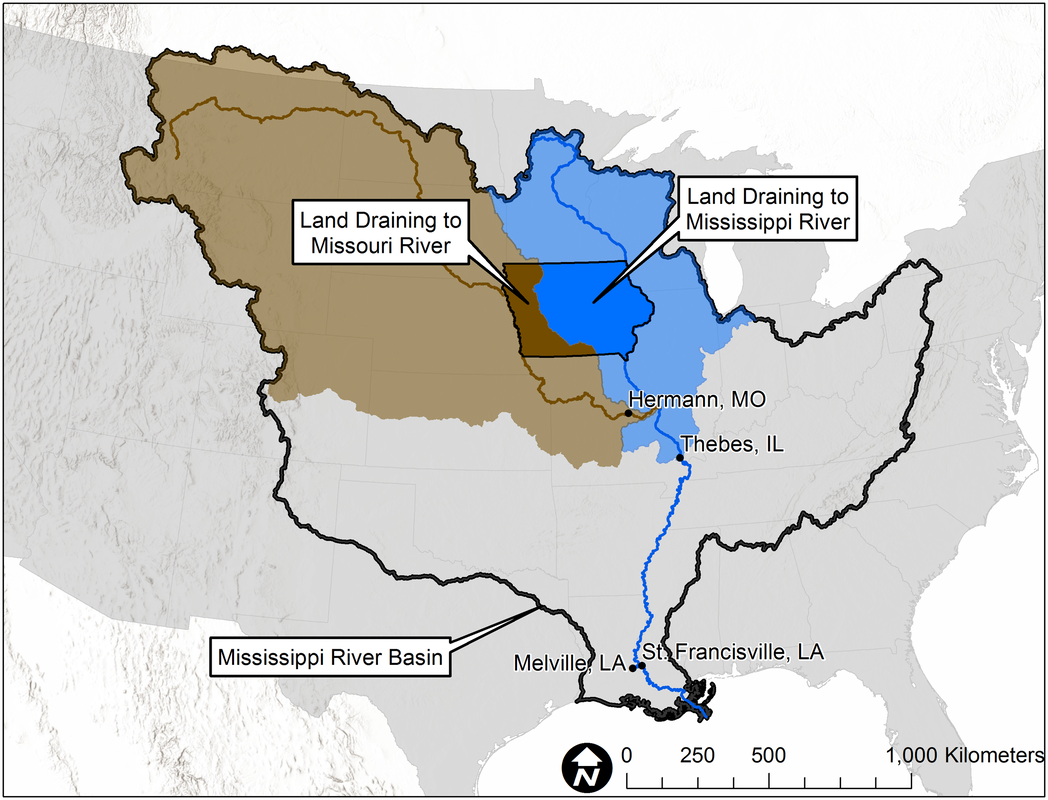

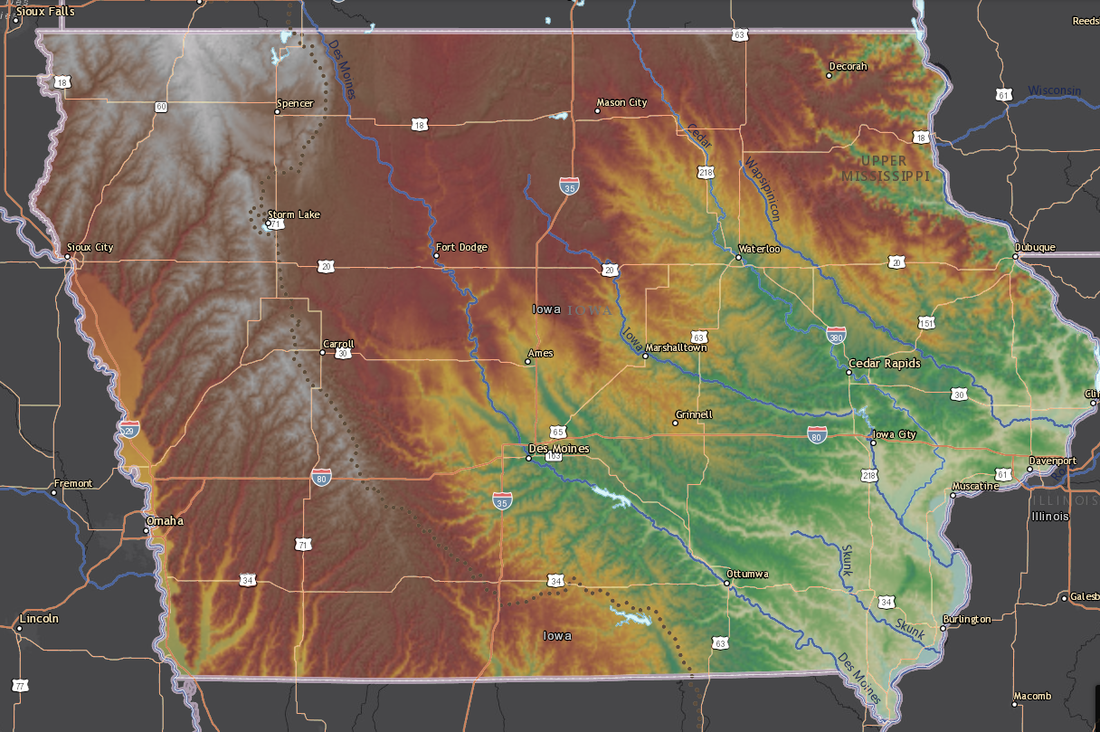

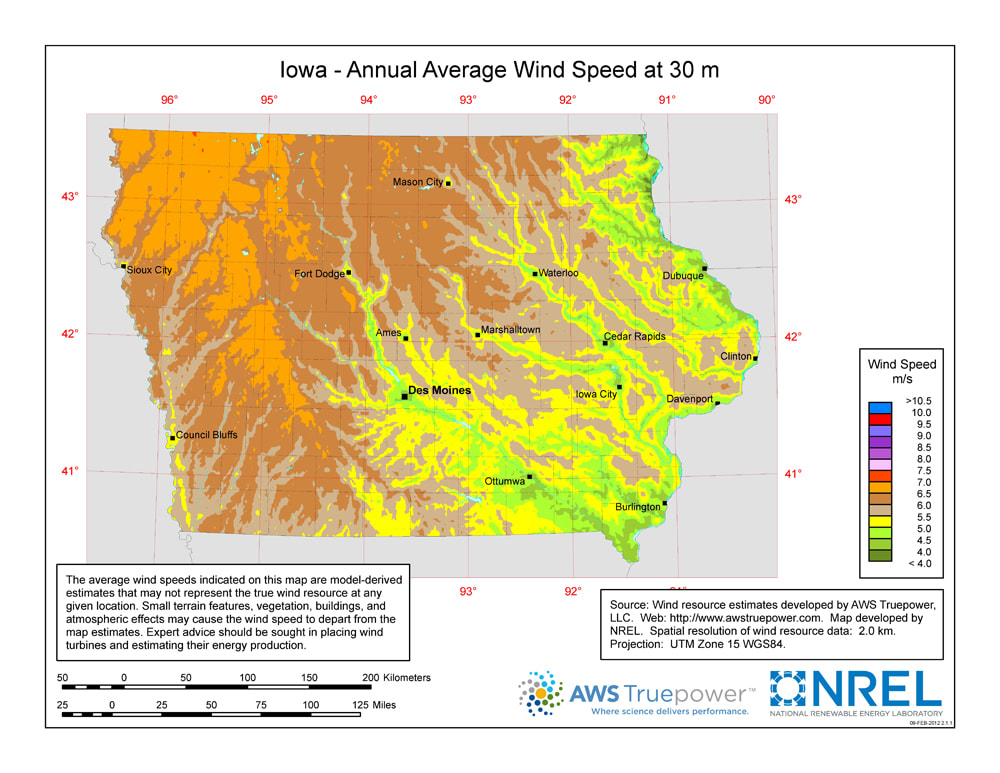

The landscape of western Iowa was formed primarily by wind and water. Several distinct landforms are visible along Western Skies Scenic Byway, which parallels Interstate 80 through Harrison, Shelby, Audubon and Guthrie counties. The Loess Hills are deposits of aeolian (wind-blown) silt up to 200 feet high. The Hills parallel the wide, flat Missouri Alluvial Plain immediately to their west. Some of the larger river valleys also feature flat, relatively wide floodplains.  The Loess Hills near Missouri Valley in Harrison County. The flat Missouri Alluvial Plain is in the background on the left side of the photo, and the Boyer River Valley is the flat area on the right side. The city of Missouri Valley is located at the confluence of these two valleys. Photo taken by Lance Brisbois at Old Town Conservation Area. East of the Loess Hills lies the Southern Iowa Drift Plain. Here, streams and rivers have carved valleys, resulting in a rolling landscape. Driving west to east along Western Skies Scenic Byway, you will almost always be going up or down. On the eastern edge of the Byway is the Des Moines Lobe. This area was covered during the most recent glaciation, and the land is mostly flat. It was home to many wetlands and small lakes called prairie potholes, though most of the land has been drained for cropland. Around Panora and to the north and east, you will notice the landscape is much less rolling than it is to the south and west. Retreating glaciers left terminal moraines, or visible ridges where the glacier stopped advancing. A terminal moraine is visible in northern Guthrie County near Whiterock Conservancy. Whiterock is also home to a kame, which is a gravelly mound deposited by the retreating glacier. Wind and water also contributed to historic and current vegetation and land use. Most of the landscape was prairie, with scattered savanna and open woodlands. The Missouri River and other floodplains had some dense stands of forest. A few places in the steep Loess Hills were fairly wooded. The Des Moines Lobe was primarily wetlands with countless ponds and small lakes. Nearly all of the prairies and wetlands have been converted to cropland, except for the steepest areas where farm machinery cannot safely navigate. Many of those areas are instead grazed or hayed pasture now. More than half of Iowa's remaining prairies are located in the Loess Hills.  Modern land uses and vegetation along Western Skies. Tan is cropland, orange and gold are pastures, green is woodland. Notice how well the cropland aligns with the prairies, except for the steepest areas that are now mostly pasture. Source: Iowa Geographic Map Server (https://isugisf.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=47acfd9d3b6548d498b0ad2604252a5c) Over several thousand years, drainage networks formed throughout the region, creating small streams, larger rivers, and watersheds. A watershed is the area of land that drains into a specific body of water. Watersheds are categorized by Hydrologic Unit Codes (HUCs) based on their size. HUC-8 watersheds are larger, including the Boyer & Mosquito in Harrison County, West Nishnabotna in Shelby County, East Nishnabotna in Audubon County, , and the Raccoon in Guthrie County. Tributaries of the HUC-8 rivers are HUC-12 watersheds. Driving from east to west, you will cross a new HUC-12 watershed every few miles. West of Guthrie Center on Highway 44, you will cross the Missouri-Mississippi watershed divide. Rainfall and snowmelt on the east side of this subtle ridge eventually flows into the Mississippi River, while water on the west side of the line makes its way into the Missouri River. Although barely visible, This divide separates two of the largest river systems on the continent. As you cross the divide, notice how streams change from flowing southwesterly on the west side to southeasterly on the east side. The drainage and valley patterns are believed to have contributed to pre-colonization vegetation. Hot, dry southwest winds likely carried fire longer distances up the river valleys and ridges west of the M&M divide. East of the divide, streams ran perpendicular to the prevailing winds, each offering a barrier to fire systems. The Missouri-Mississippi divide is generally a line of highest elevation from northwestern to south-central Iowa.  Elevation map of Western Skies counties. Green is lowest (river valleys), then yellows, reds, and gray/white is the highest elevation. The M&M divide runs through the whitish area. Map source: : Iowa Geographic Map Server - https://isugisf.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=47acfd9d3b6548d498b0ad2604252a5c These relatively higher elevations offer some of the greatest wind energy potential in the state. Driving across the Byway, you will likely see some wind farms in addition to the many historical windmills dotting the landscape. Next time you visit Western Skies Scenic Byway, try to identify the landforms and watersheds and note how wind and water have shaped the land over time!

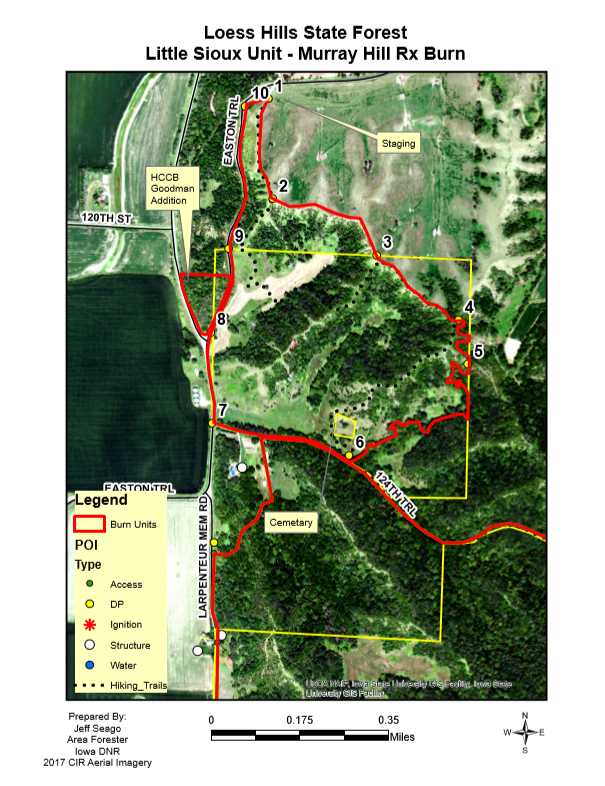

On Thursday, September 3, wildland firefighters from six conservation organizations conducted a prescribed burn at Murray Hill Scenic Overlook and Loess Hills State Forest in Harrison County. Many people have gotten used to seeing spring and fall burns, but early September has not been a common time to burn. Due to the severe drought in western Iowa, fuels are especially dry this year and burned exceptionally.

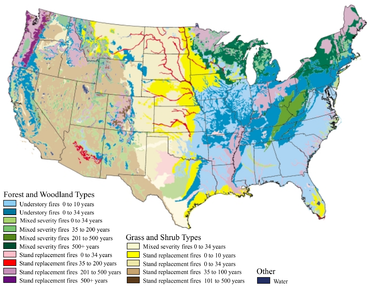

Local agencies have started conducting more late summer (growing season) burns to see how the results compare to fires at other times of year. There is evidence that fire may have historically been prevalent at this time of year due to lack 0f rainfall and prevailing dry, southwesterly winds in late summer. The primary goal of growing season burning is to set back woody vegetation (trees and shrubs) that can invade and take over the remnant prairies. Loess Hills prairies evolved over thousands of years with regular fire regimes. Some were started by lightning, and more were started by indigenous peoples to improve habitat for hunting and food production. Fires likely swept through the Loess Hills once every few years, possibly even annually. After European colonization, fires largely ceased and trees encroached onto the grasslands. Fire may have been used as a management tool for as long as people have lived in the Loess Hills, but conservation groups have only realized its importance within the past few decades.

To start the day, the crew met and reviewed the plan for the day. The main unit included Murray Hill Scenic Overlook on the north side, bounded by Easton Trail (county blacktop road), following a ridgeline to the southeast and including a portion of the adjacent Loess Hills State Forest to the south. Brent's Trail, a popular new hiking trail, runs through this unit.

Firebreaks were cleared a day before the burn to provide clear boundaries within which the fire would be contained. Firebreaks can include mowed paths, roads, waterways, or other barriers that will not readily burn.

Firefighters broke into four divisions for different tasks. Fires were ignited from different sides to burn into each other. Firefighters watched the lines to ensure fire stayed within the burn unit. The unit included prairies, woodlands, and pasture with different fuel types and topography, each with their own unique fire behavior.

After the Murray Hill fire was completed, the group burned a four-acre unit that was recently acquired by Harrison County Conservation Board immediately west of Murray Hill. This steep area included hillside covered with eastern red cedar trees, which can become problematic and invasive when not kept in check with fire and grazing animals. The cedars tend to crowd out other native prairie species and create a coniferous monoculture.

Since the trees were so dry, many torched rapidly leaving only charred trunks and branches. These cedars will not grow back, and the prairie seed bank in the soil will flourish with the sunlight that is once again able to reach the ground.

The photos below show the landscape one day after the burn. Most of the prairie grasses and flowers are gone, but since the prairies evolved with fire, the hillsides will quickly turn green next spring. Some plants will even reemerge within the next week or so. Local land managers are hopeful that this fire will help restore a thriving, healthy prairie ecosystem that has not seen a growing-season burn in many decades.

For more information about prescribed fire. visit the links below.

More than 99.9% of Iowa's native prairies have been been removed from the land. Of the remaining <0.1%, more than half is located in the steep Loess Hills landform of western Iowa. Prairies evolved over thousands of years with regular fire regimes set by native peoples and lightning. Large ungulates like bison also roamed the prairies, grazing grasses and forbs. Since European settlement in the 19th century, the fires and grazers have largely been eliminated from the landscape. In recent years, fire has seen a resurgence as an important tool for prairie, savanna, and woodland restoration and management.

Partners from Iowa Department of Natural Resources and local county conservation boards joined to help burn hundreds of acres of public and private lands in Monona County on April 30, 2020.

The annual Loess Hills Cooperative Burn Week had been scheduled for this week but was postponed due to COVID-19. Burn Week partners are still making the best of available resources, and conservation agencies regularly collaborate to assist with burns on both public and private lands throughout the Loess Hills. After an overview of the plan for the day and weather conditions that morning, three squads separated to their respective units. Firefighters used drip torches to light areas within the fireline, including both woodlands and grasslands. Roads, water bodies, and mowed paths are often used for firebreaks to contain the fire.

Without fire and grazing, eastern red cedar (juniperus virginiana) can take over and crowd out other species. Although these cedars are a native species, they rapidly become invasive without proper management.

Cool-season grasses like brome that were planted as pasture for livestock can also take over native prairies.. Brome does not have the same habitat value as a diverse remnant prairie. Cool-season grasses green up earlier than warm-season grasses. Burning in spring can set back the cool-season grasses that have started to green up, and help natives recolonize an area.

Perennial native vegetation is fire adapted so burning does not kill it. Native plants burn more quickly and thoroughly than brome pastures. Flowering plants in the burn unit will bloom slightly later in the season than in unburned portions which extends availability of nectar resources for pollinators. Many flowering plants will have more flowers and seed production during the year of the burn (=more nectar resources and more food resources). In woodlands and savannas, bur oak trees are fire-adapted but many shade-tolerant species are not. Prescribed fire favors native oaks by removing seedlings of other shade tolerant species like hackberry. This time of year, people may wonder about the effects of fire on grassland ground-nesting birds. Since they evolved with the prairie and fires, they have strategies to adapt and are very persistent re-nesters. If they lose a nest to a fire, they will re-nest. In order to keep the whole grassland functioning long term, prescribed fire is necessary along with some short term-losses of nests. Natural areas are broken up into units so that the whole area doesn't have fire at the same time. A burn unit may only see one fire every 3-7 years, though some areas are burned more frequently.

To protect crop land near the burn units, corn stubble was removed from the outer edge of fields. Much of the prairie to be burned is on top of the Loess Hills ridges, while lower areas are cultivated rowcrops. The blackened area won't last long, as green prairie plants will begin to dot the landscape within a few days.

The diversity of the burn unit offered ample opportunities to see how fire behavior varies with fuel, topography, and weather changes. When a large brush pile caught fire in a ravine, flame lengths reached 30 or more feet! Most of the fires, however, were only a few inches to a few feet tall.

In addition to the ecological and wildlife habitat benefits, prescribed fires help maintain the unique Loess Hills scenery along the viewshed of the Loess Hills National Scenic Byway. This fire was located on the Wilderness Loop of the byway in Monona County, which includes some of the most rugged and remote parts of the state. Firefighters posted signs on the road to warn drivers of possible smoke, and to let people know that the fires are intentional.

While you're out exploring the Loess Hills this spring, don't be surprised if you see smoke and flames. It is probably a prescribed fire being used to restore our fragile and globally-significant Loess Hills!

For more information about prescribed fire in the Loess Hills, visit the Loess Hills Alliance's Stewardship Committee web page. Iowa Western Community College Greenhouse Initiative receives Presidents' Engaged Campus Award4/16/2020 Iowa Western Community College in Council Bluffs has been awarded the Presidents' Engaged Campus Award for the Greenhouse Initiative, a partnership with several partners including Golden Hills. Golden Hills is excited and grateful to be part of this effort and congratulates Iowa Western and all our partners. Golden Hills is using space in the greenhouse for growing native prairie plants as part of our Prairie Seed project. Earlier this year, we had two educational workshops on campus with more than 40 people who learned about growing native plants. At the classes, we started seeds in the greenhouse and intend to have a native plant sale this spring. Learn more about the project and partners in this video. The Presidents’ Engaged Campus Awards recognize, celebrate, and tell the story of great individuals, projects, and programs in both Iowa and Minnesota. Through the presidents’ awards categories every campus has the opportunity to recognize students, faculty & staff, and partners leading the way in their campus community. We also have selective award categories to showcase innovation, collaboration, employer partnerships, and civic-minded alumni.

Nominations were submitted by member campuses and partners, and scored by independent reviewers. Twelve projects were selected for 2020 awards. The greenhouse initiative won in the category of Emerging Innovation: A recent project, program or initiative making unique and innnovative contributions that demonstrate strong future potential, including student-led projects. Learn more about the Presidents' Engaged Campus Awards here and read their official press release about 2020 awards. here. Below are a few photos of the classes and the plants currently growing in the greenhouse. Learn more about this project at goldenhillsrcd.org/prairieseed By Bill Blackburn While U.S.-China relations have been tense recently when it comes to international trade, one area that has witnessed a new era of collaboration and cooperation between the two countries is the study of the Loess Hills. In June, a small gathering of U.S. and Chinese experts on loess soils and restoration met in Yangling, Shaanxi, China to share information on the Iowa Loess Hills and China Loess Plateau, their condition, value, restoration and protection, as well as the latest research on loess soils. Loess (pronounced as “luss,” “Lois,“ or “less”) is a yellowish deposit of wind-blown rock dust found in Germany, Argentina, New Zealand, U.S., China, and many other parts of the world. However, it forms hills of significant height (60-350 feet) only in two places: in the Yellow River region in and around Shaanxi province, China, and in the mini-mountains (bluffs) in the Midwest U.S. that parallel the Missouri River 220 miles from Mound City, MO to Westfield, IA. In Iowa, the beautiful sharp-cliffed hills can be seen along Interstate 29 through the western sides of Fremont, Mills, Pottawattamie, Harrison, Monroe, Woodbury, and Plymouth Counties. They were formed from glacier-ground rock powder brought down the Missouri River and blown into dunes by westerly winds. The Chinese “Loess Plateau,” which covers an area only slightly less than the entire state of Texas, is located several hundred miles southwest of Beijing. The loess there eroded from various mountain areas over millions of years, was collected in the Gobi and other deserts, and from there was blown into the plateau. Over the centuries, the Loess Plateau, had become massively eroded from overgrazing and deforestation, with the resulting erosion filling the Yellow River with deposits of so much loess that devastating flooding of croplands became common. A huge restoration project funded largely by the World Bank and others set out to partially restore the plateau over an area roughly the size of New Jersey. The June U.S.-China Exchange on Loess Landforms came about as a result of a lecture series on the Loess Plateau done in Western Iowa and Omaha in 2017 by John Liu, a Chinese-American documentary film-maker from Beijing, who had recorded the dramatic conditions of the Plateau before and after restoration. Acclaimed soil scientist Professor Robert Horton of Iowa State University worked with his long-time friend, senior Professor Baoyuan Liu (no relation to John) and Professor Fan Jun, both soil scientists at China’s Northwest University of Agriculture and Forestry, to have NWUAF sponsor the meeting. The Gilchrist Foundation, which co-sponsored John Liu’s 2017 lecture tour, also funded the participation of young professionals, Graham McGaffin, of the Nature Conservancy-Loess Hills, Sioux City, and Assistant Professor Bradley Miller of Iowa State. Also participating from the U.S. were Professor Michael Thompson of Iowa State, and Bill Blackburn of the Green Hollow Center in Fremont County. Presentation were also given via the internet by Professor Tom Bragg, plant specialist from the University of Nebraska-Omaha, and John Thomas, loess erosion expert from the Hungry Canyons erosion control program at Golden Hills RC&D in Oakland. Besides the one-day conference in Yangling, the U.S.-China delegation also visited NWUAF soils research stations in the Loess Plateau near Chang Wu and Ansai to review their latest research projects. The tour was capped off with a visit to the famous terra cotta warriors of the Qin Dynasty Emperor that were buried near Xian in the Plateau around 200 BC---warriors we were surprised to learn were made of loess soil glued together with rice water. The agenda and presentations offered at the Exchange and pictures from the tour of the Plateau can be seen on the Golden Hills RC&D website ( www.goldenhillsrcd.org/ucell.html). A follow-up meeting in Western Iowa is now being considered. In fall 2018, we partnered with Pottawattamie County Conservation and Iowa Prairie Network on events for native prairie seed harvest. In 2019, with support from Gilchrist Foundation, we are expanding these efforts throughout the Loess Hills.

We will work with local partners to find volunteers for the project. Volunteers will visit local prairie remnants and learn how to identify which plants are available for seed collection. The harvested seed will then be used for local prairie restoration and reconstruction projects. We anticipate at least monthly seed harvest workshops from May through October at several sites in the Loess Hills and will be looking for volunteers. If you are interested, fill out this form. Check the project website for more details as they are confirmed! We are partnering with West Pottawattamie Iowa State University Extension and Outreach and Pottawattamie County Conservation to offer the Iowa Master Conservationist Program starting Spring 2019. The program will take place primarily at Hitchcock Nature Center, providing participants with hands-on interaction with the diversity of the state’s natural resources. The program teaches about Iowa’s natural ecosystems and the diversity of conservation challenges and opportunities that exist in the region. Graduates of the course learn to make informed choices for leading and educating others to improve conservation in Iowa.

The program consists of approximately 12 hours of online curriculum and six face-to-face meetings. The online modules will include lessons and resources by Iowa State subject-matter experts to be reviewed at the participants’ own pace at home or at the ISU Extension and Outreach West Pottawattamie County office. Module topics include conservation history and science, understanding Iowa ecosystems, implementing conservation practices in human dominated landscapes and developing skills to help educate others about conservation practices. Six face-to-face meetings will build on the online lessons and be held at Hitchcock Nature Center from 8:00 a.m. to Noon on the 4th Saturday of the month starting April 27th and ending September 28th. Each face-to-face meeting will be led by local subject-matter experts to demonstrate how the principles covered in the online curriculum and play out locally. Participants will work with program partners Golden Hills RC&D, Pottawattamie County Conservation, Pottawattamie County Soil & Water Conservation, Pottawattamie County NRCS, ISU Extension and Outreach West Pottawattamie, along with educational experts in their fields. Registration for the course is $100/participant or $50 for college and high school students with a valid school ID and is due at the time of registration. To register contact the ISU Extension and Outreach West Pottawattamie County office at 712-366-2646. The deadline to register is April 19th at 4:00 p.m. Contact: Carol Waters County Director ISU Extension and Outreach—West Pottawattamie County 712-366-7070 [email protected] Related Websites: |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Address712 South Highway Street

P.O. Box 189 Oakland, IA 51560 |

ContactPhone: 712-482-3029

General inquiries: [email protected] Visit our Staff Page for email addresses and office hours. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed