|

By Doug Chafa

(Please note this post is part of the Loess Country series) Named from the French word “becheur” which means, “digger,” badgers live in grasslands and do well on the edges of fields and forests. While they are found in all 99 of Iowa’s counties, badgers are more numerous in southern and western Iowa, and are particularly attracted to the native prairie, pasture, oak woodlands and farmland in the loess hills. This iconic grassland predator is armed with 2 ½-to 3-inch claws on its front paws and known for its powerful and fierce disposition. This mammal has a grizzled gray fur color with short stout legs. Its facial markings are distinct, with black badges and white stripes on its cheeks and a white stripe from the nose to the neck. Its ears are set wide on the side of its head. It is primarily nocturnal and fossorial, which means spending time underground in dens. These fearless carnivores are in the mustelidae family that includes weasels and mink, and have the musky odor common among the members of this family. Badgers have been known to eat gophers, ground squirrels, mice, snakes, frogs, and toads and are one of the few predators of skunks. They will eat ground nesting birds, their eggs, and nestlings and will scale banks to dig out and eat bank swallow nestlings or eggs. Badgers can dig a large number of burrows searching for pocket gophers. While the burrows can be hazards to machinery and livestock, badgers do provide a significant amount of rodent control. Mating season stretches from late summer into the fall. Badgers have delayed implantation where the fertilized embryo doesn’t start development until February. Two to three kits are born early in the spring, blind and covered with fur. Their eyes open at four weeks and the kits are weaned at eight weeks. The young disperse late summer through early fall and can be spotted during the day. The young are less alert to roads and vehicles so many are hit on highways. Instead of hibernating, badgers use long cycles of sleepiness during the winter which reduces their expenditure of energy and need to forage. They can be seen in the winter as they occasionally exit their dens on days when the temperature is above freezing. Badgers have a well-earned reputation as being aggressive and fierce. They snarl, hiss, and growl when confronted, often making a series of short bluff charges at perceived threats before retreating to the safety of a den. I stumbled upon a pair of fighting badgers as a kid and it was one of the loudest and most savage fights I have ever witnessed. They were oblivious to my dog and me as they circled and snarled and tangled with each other with vicious bites and wrestling. Badgers have very loose skin which allows them to turn and bite back, even when an attacker is biting and pulling on them. Adult females weigh up to 14 pounds and males can hit 30 pounds. They have few predators in western Iowa, but in western states, mountain lions, wolves, and bears have been known to kill adult badgers. Young badgers are occasionally taken by golden eagles and coyotes. The badger’s earthworks are useful to other wildlife and plants. Some animals, like coyotes, groundhogs, and foxes, make use of badger dens and burrows. Burrowing owls have been known to nest in badger burrows. Snakes and toads use the burrows to cool during the heat of warm days. Mounds of dirt excavated by badger burrowing create bare soil for prairie seeds to colonize. So while you may or may not ever see a badger, most likely you’ve seen its handiwork.

0 Comments

Learn more about what we've been up to in our 2018 Annual Report below. If you like our work, please consider donating to Golden Hills for Giving Tuesday on Tuesday, November 27!

"Celebrated on the Tuesday following Thanksgiving (in the U.S.) and the widely recognized shopping events Black Friday and Cyber Monday, #GivingTuesday kicks off the charitable season, when many focus on their holiday and end-of-year giving." As a small nonprofit, we rely on support from generous donors like you to fulfill our mission of developing and promoting sustainable cultural and conservation projects that enhance the quality of life and preserve the assets of rural western Iowa. You can make a one-time donation or set up recurring donations through our Omaha Gives account. All donations are tax-deductible. You can also support Golden Hills on any day of the year through an online donation at http://www.goldenhillsrcd.org/donate.html Thank you for your support! By Bill Blackburn

(this post is part of the Loess Country series. Check back soon for more!) The Office of the State Archaeologist at the University of Iowa can tell an interesting story about the early peoples who first settled the Loess Hills of Western Iowa. Humans first arrived in the Hills around 11,500 B.C. to 8,500 BC, not long after most of the loess sediment of ground rock powder from northern glaciers was wind-deposited to form the hills. These so-called Paleoindians were nomadic hunters of bison and other large game. The Archaic peoples that followed from 8500 BC to 1000 BC were nomadic hunter-gathers but made greater use of semi-permanent base camps and smaller seasonal camps. The Woodland Indians (1000 BC to 1250 AD) were more sedentary, living in small hamlets of structures that were earth-covered or wattle-and-daub construction (woven lattice of wooden strips--wattle– that was daubed with a sticky material usually made of some combination of wet soil, clay, sand, animal dung and straw). Over 130 of these lodge home sites are being protected within the 900-acre Glenwood Archaeological State Preserve, now under development. These people made pottery, hunted deer and small game, cultivated corn and squash, and gathered wild berries and seeds. They prospered for approximately 300 years, disappearing from the archeological record around 1300 AD due to extended drought, according to some experts, or because the threats of Oneota Indian raiders (predecessors of the Ioway and Otoe tribes), according to others. The Oneota were about the only Indians roaming the hills from 1300 AD to until the 1700s. Then the Ioway Indians (called Ayauway by Lewis and Clark) and ancestors of the Pawnee began to appear. Hunting parties from the Otoe and Omaha tribes that lived on the east side of the Missouri River also started venturing to the Iowa side and into the Hills. The nomadic Dakota Sioux traveled the river, roving the territory on both sides. In 1837, the Potawatomi Indians (also spelled “Pottawattamie” or “Pottawatomie,” a traditional word meaning “Fire Keepers” or “Keepers of the Council Fires”) were relocated from Indiana and Illinois to Missouri and ultimately to Western Iowa. They remained there with their great war chief, Waubonsie (also spelled “Waubonsee” or “Wabaunsee”) until 1846-48, when, in response to pressures from growing pioneer settlements, they were moved to Northeast Kansas. It was about this time that the great Mormon Migration from Nauvoo, IL arrived in Western Iowa. Of course, the Mormons were not the first European-heritage pioneers to show interest in the Hills. French fur traders began exploring the region in the early 1700s. On July 16, 1804, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark observed this unusual landform as they came up Missouri River. Clark recorded in his journal: “This prairie I call the Ball pated (sic: bald headed) prairie from a range of ball hills parrell (sic) to the river from 3 to 6 miles distant & extends as far up the down as I can see.” At that time the Loess Hills had remained generally treeless except for a few oak savannahs due to the drier climate and repeated prairie fires. Artist George Catlin traveling by steamboat up the Missouri River in 1832 went ashore to climb the Loess Hills and described the place as one where a “thousand velvet-covered hills go tossing and leaping down with steep or graceful declivities.” A mere few decades later, new settlers were giving birth to the farms and communities that continue throughout the Hills to this day. By Ryan Allen

(This is part of the Loess Country series--check back for more soon!) BLOOM is what I think when I look my little girl in the eyes as I hold her. This little one, the first bud of a compass plant, waking up in a dew-soaked prairie, a new life in my hands and arms-- at first hanging so purple cocooned between caterpillar and butterfly, between a breath a cry and a shiver to shake off the fall leaves circling in wind, now so content to eat and poop and pee and love. I learn new ways to kneel and pray. What we plant is what we grow. And the sky is spinning forever and raining the yellowest leaves around my little girl’s cry. O! Prairie! O! Wind! O! Life!, carry us to that piece of earth where all our flowers can bloom. By John Thomas, Project Director and Fluvial Geomorphologist for the Hungry Canyons Alliance. This article is part of the Loess Country series--check back for more soon!

Erosion control or stabilization of deep gullies in the Loess Hills is challenging since filling the gully and excavating a core trench in an area of such deep ravines is often cost-prohibitive. The only practical way to stop gully erosion is with a pipe-drop structure that passes water runoff from the top to the base of the gully through a pipe. The Hungry Canyons Alliance (HCA), in conjunction with the USDA-Natural Resource Conservation Service, is using directional drilling techniques to bore a hole at an angle through the loess soil from upstream of the headcut to the base of the gully wall. Polyethylene (PE) pipe is inserted at the base and pulled back up through the bore hole from downstream to upstream. The slurry used to drill the hole acts as a sealant between the pipe and soil making the borehole watertight as it dries. A vertical perforated PE riser is added to the angled drainage pipe to serve as an inlet. A water-retention basin is excavated upstream of the inlet, and a dam or terrace is built downstream between the inlet and the headcut of the ravine to collect water for gradual drainage through the riser and pipe. The basin allows a larger storm event to be controlled by the small drainage pipe. No filling or other work is done in the gully, dramatically reducing earthwork costs. The near-vertical gully slopes will gradually slump to a stable slope over time because collapsed debris will not be carried away by surges of runoff. Twelve of these experimental Bored Headcut Basin (BHB) structures have been built in the Loess Hills since 2007 to control 20 – 80-ft deep gully headcuts with small drainage areas (0.5 – 37 acres). These BHB’s have averaged only about $11,000 to build, with a maximum of around $17,000. They have weathered up to 4-inch rain events without incident. Considering that a traditional pipe-drop structure may cost as much as $60,000, the BHB has proven very cost-effective. HCA continues to monitor the progress of these structures while planning future BHB projects. If you are interested in controlling gully erosion on your property, please call your local USDA-NRCS office. Cost share for these projects have averaged 78%, so the average landowner cost for these projects has been only about $2,400. Plus, the USDA-NRCS provides survey and design assistance. Golden Hills staff will be presenting at the Draft Meetup this Thursday evening at Barley's in Council Bluffs, discussing the many projects we do to build bikeable communities, develop regional trail systems, and promote bicycle tourism in southwest Iowa.

DRAFT is a nationwide meetup series that taps into people who love bikes, biz and beer. Our events bring communities together to celebrate the latest bike industry innovations. Speeches, announcements and conversations allow business leaders, product developers, tech innovators, advocates, artists and more to share big ideas—all while enjoying delicious craft beer. Join us for a fast-paced event of ideas, entrepreneurs and bikes, capturing the exciting things happening in the bike industry at DRAFT: Iowa in Council Bluffs at Barley's Bar and Grill. Hosted by the Iowa Bicycle Coalition and RAGBRAI. The event is free but registration is requested. Register here! Barley's will be providing pizza as an appetizer for all registered attendees! Speaker Lineup: Pete Phillips - Pork Belly Ventures Vince Asta - Ponderosa Cyclery Julie Harris - The Nebraska Bicycling Alliance Lance Brisbois - Golden Hills Program: 6:00 - 6:30 pm: Beer and banter. 6:30 - 8:15 pm: Program + Speakers 8:15 - 9:00 pm: More beer and banter We hope to see you there! We've been working with Pottawattamie County staff to photograph the water trail using Mapillary. The imagery provides a 360° view of the West Nish Water Trail in Pottawattamie County. We have currently completed Avoca to Carson and hope to finish Carson to Macedonia in 2019. The images can be useful to paddlers and tourists, as well as to landowners and farmers along the river. It will be useful long-term to see how the river changes over time. It will also be a good way to imagine being on the river this winter when it's too cold to get out there!

A few sample images are below. Click here to see more. By John Thomas, Project Director and Fluvial Geomorphologist for the Hungry Canyons Alliance. This is part of the Loess Country series--stay tuned for more!

Loess soil isn’t rare; what’s rare is the fact it is so thick in the Loess Hills along the Missouri River of Western Iowa. This thickness and the distinctive physical properties of loess make the Loess Hills a truly unique landform. Loess is made up of pre-dominantly silt-sized quartz grains that are calcareous (chalky), porous, and lightweight, which cause it to be very cohesive when dry but easily eroded when wet. Vertical faces of loess in road cuts and gully walls have been known to stand for more than a hundred years, in contrast to loess slopes, which are prone to some of the highest erosion rates in the country. Old U.S. Geological Service records show a stream gage in Waubonsie Creek in the Loess Hills (Mills and Fremont Counties) recorded 2.7 pounds of sediment per gallon of water in 1947, almost three times higher than any other suspended sediment load measured on any other Iowa stream in history. Also unique to the Loess Hills are the stair-like features found on very steep slopes called cat-steps. Gravity and water cause small rotational slips to form long, narrow benches, about a foot wide, with vertical scarps – like a flight of stairs – across the hillsides. The deep loess soils, steep slopes, and propensity for erosion by water have created a high number of stream channels per square mile in the Loess Hills. Many of these channels are gullies that have cut deeply into the landscape, some reaching depths of more than 80 feet, and having near-vertical side walls with a semi-circular headcut, or overfall, at their upstream end. Gullies expand and erode upstream during rainfall when either surface runoff, entering the gully via the headcut, or groundwater flow, entering the gully at the base of near-vertical walls, de-stabilize the gully walls causing bank collapse. Runoff then carries away the collapsed bank debris, preparing the walls again for collapse. While some of the larger gullies were likely present before Western Iowa was first settled in the 1850’s, many of the gullies we see today began after widespread unsustainable agricultural use on the steep, erosive uplands in the late 1800’s to mid 1900’s. The channels cut down even further after many streams in Western Iowa were straightened from 1900 to 1950. Dams, flumes, and other types of structures have been constructed throughout the Loess Hills to try to halt this channel degradation that has been so destructive to this unique landform. We are excited to announce that we were recently awarded a $25,000 grant from the National Park Service and Outdoor Foundation for interpretation and programming along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and Loess Hills National Scenic Byway through western Iowa. Golden Hills staff will work with regional National Park Service staff and byway stakeholders to inventory, update, and install interpretive panels at historic, cultural, conservation, and recreational sites in the Missouri River-Loess Hills corridor.

The project proposal includes two new interpretive signs in each of the counties that the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and Loess Hills National Scenic Byway have in common (Woodbury, Monona, Harrison, Pottawattamie, Mills, and Fremont). Three additional signs will also be placed in the six-county corridor, at locations yet to be determined. Most of the signs will replace existing exhibits which are several years old and weathered, with new panels containing updated content and designs to better engage visitors. In addition to the educational exhibits, Golden Hills will host three public educational events about Lewis and Clark and the Loess Hills during 2019. The National Park Service Challenge Cost Share Program supports projects that “promote conservation and outdoor recreation, environmental stewardship, education, youth engagement” on sites administered by NPS, which includes the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. Details about the project, including photos, can be found here. For more information, contact Loess Hills National Scenic Byway Coordinator Becca Castle at [email protected] or 712-482-3029. By Bill Blackburn

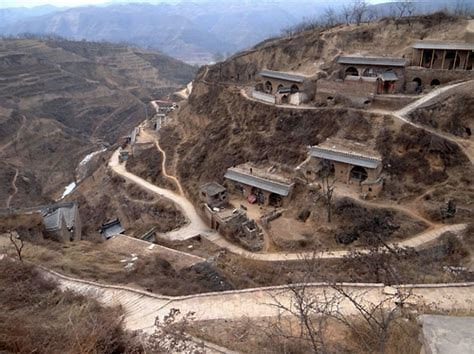

(second in a series of Loess Hills articles. Stay tuned for future posts!) Want to cut your energy bills dramatically? Build a loess home. One catch is that you have to be in the Loess Hills region which runs through Western Iowa, or in the Loess Plateau of north central China. Those are the only places where loess soil (generally a mix of wind-blown rock powder and organic humus) is found in deep deposits of 60 to 350 feet sufficient to make noteworthy hills. In both locations, the loess exhibits its unusual structural properties, which are evidenced by sheer cliffs of 50 to 100 feet or more. The material is also a good thermal insulator—cool in summer, warm in winter. So it’s no surprise that over the years, various people of limited means found it good for making homes. Native Americans in the Glenwood, Iowa region and elsewhere in Iowa’s Loess Hills often built earth lodges, with support columns of logs covered with smaller wooden limbs or reeds and then mounded with loess soil and grass. Until a few years ago, a reconstructed lodge of this type could be seen at Glenwood Lake Park. Early pioneers to Western Iowa often created “dugouts” burrowed into a loess hillside, with a wooden front wall with door and maybe a window, and ceiling support timbers. The excavations of several pioneer dugouts—a former blacksmith shop, a barn and a cellar--are still visible at the Green Hollow Center, my nature preserve in northern Fremont County. My father, who grew up in the loess hills near that location in the 1920s and 30s, often visited people living in such structures in the Hollow. He said they were simple dwellings, a bit claustrophobic for new guests, occasionally visited by burrowing wildlife, but pleasantly climate controlled. In the Loess Plateau of northern China, prehistoric peoples were living in underground loess dwellings as early as the Chinese Bronze Age, the second millennium BC. It’s estimated that loess homes, called yaodongs or “cave houses” are still being used by an estimated 40 million Chinese. Three types of yaodongs can be found. Cliffside yaodongs are dug into the side of a loess cliff, creating a flat floor and arched roof. The front of the cave has one to three holes for lighting and ventilation. Sunken yaodongs or “pit yards” are constructed by digging a large square pit that serves as a courtyard, then excavating caves into the sides of the pit. The pit is reached by an excavated ramp, or if the pit wall is not far from a cliff, by a tunnel excavated from outside the cliff through the pit wall. Hoop yaodongs are arched structures formed with most or all of the dwelling on top of the ground. As with Native American earth lodges, loess covers the outside of the hoop yaodongs, but the Chinese version often features windows high in the arch to allow light and the warmth of the sun in winter. The inside walls of yaodongs are often plastered with white lime, and the outside may have a façade of stones or brick. Yaodongs have had their place in important events in Chinese history. In 1556, an earthquake centered on the Loess Plateau in China’s Shaanxi province killed over 800,000 residents, many of whom died in collapsed yaodongs. The most famous yaodongs are those in Yan’an, which served as headquarters for Mao Zedong and his Communist leaders during the 1935-1948 resistance movement. In China, loess homes continue to be popular. With the age of “eco-design” in the U.S., perhaps we’ll see their return to the Loess Hills of Western Iowa. What’s old is new. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Address712 South Highway Street

P.O. Box 189 Oakland, IA 51560 |

ContactPhone: 712-482-3029

General inquiries: [email protected] Visit our Staff Page for email addresses and office hours. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed