|

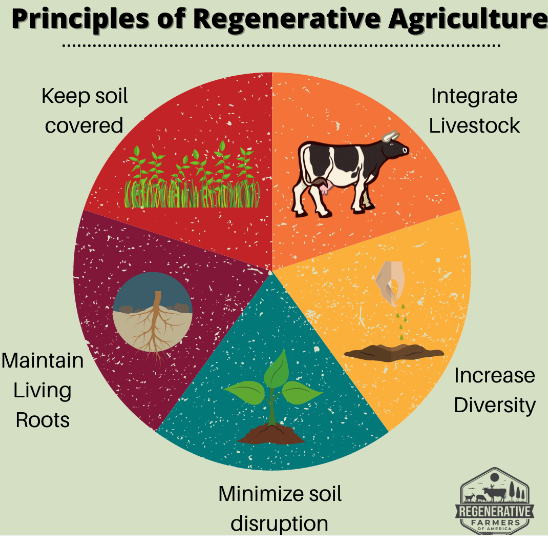

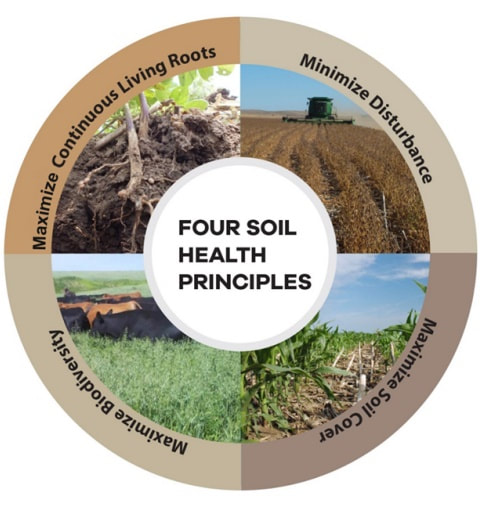

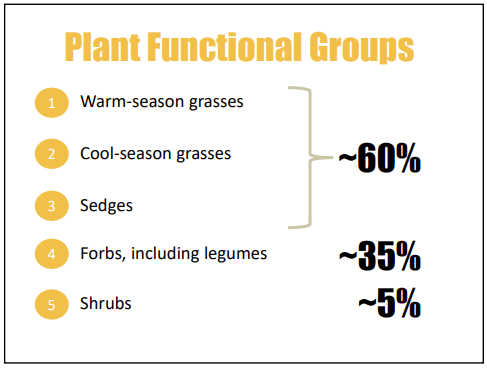

Regenerative agriculture is a buzzword you might have heard lately. But what does it mean? Check out this video from Regenerative Farmers of America to learn more: Regenerative agriculture aims to improve sustainability for land, water, wildlife, people, and rural communities & economies. While there are certainly challenges to implementing regenerative practices within current systems on a global scale, many farmers across America and beyond have begun to see the benefits of these practices. In a nutshell, regenerative practices include:

Additionally, the principle of knowing your farm's context is often included, as each piece of land is different based on things like soils, topography, and climate. Practices that work well on one farm wont' always be best on another farm. Golden Hills will be working with local farmers in the coming years to incorporate practices that build soil health and provide environmental benefits, as well as more nutritious food and help rural communities.

Stay tuned and learn more at goldenhillsrcd.org/regenag

0 Comments

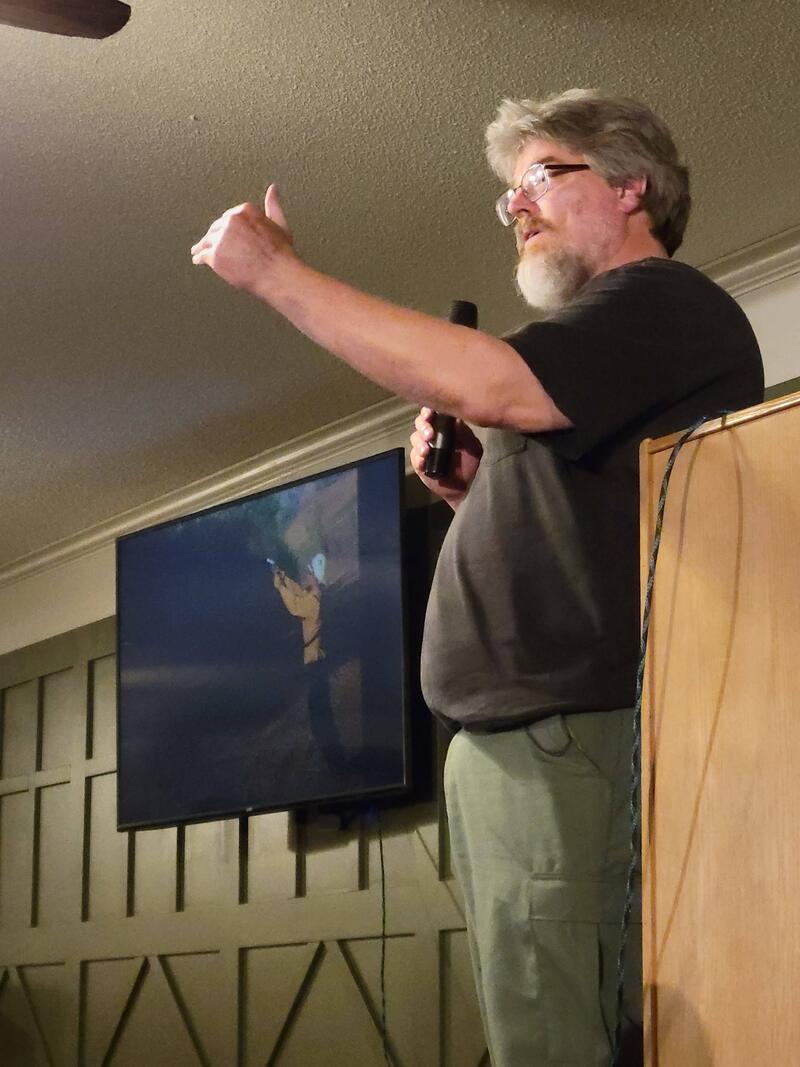

April 24-28 was the 8th annual Loess Hills Cooperative Burn Week, hosted by Loess Hills Fire Partners. This event is "an opportunity to join with partners to achieve fire management in an area where additional skills and resources were needed to accomplish the work at a landscape scale. It was also an opportunity to build relationships with partners, share knowledge and skills, and work within a more complex organizational structure utilizing an expanded Incident Command System." More than 100 people from dozens of organizations, numerous states, and even Canada, joined this year's event. The group was based out of Loess Hills State Forest headquarters in Pisgah, and burned primarily in Harrison, Monona, and southern Woodbury counties. Fire is an important part of stewardship for western Iowa's land. Historically, fires were set by indigenous peoples and occasional lightning strikes on an interval of every few years. Without these regular fires, fuels build up that pose a serious threat for more dangerous wildfires. Just two weeks before Co-op Burn Week, more than 3,700 acres were burned in the Preparation Canyon Unit of Loess Hills State Forest and adjacent private lands. Other large wildfires have burned several thousand acres in western Iowa in the past year. While Co-Op Burn Week typically involves burning large areas to meet ecological objectives, being able to put out a fire is even more important. Monday's activities focused on fire suppression. Trainers started a small fire and participants had to work together to mobilize resources to extinguish the fire. Drought conditions have made grass and woodland fires more frequent, and high winds can spread them incredibly quickly. The fire suppression activities highlighted the need for excellent communication in a high-stress, time-limited situation with people who have never worked together. Monday evening was a special event in Woodbine, featuring Brad Elder from Nebraska. Brad was badly injured in a burnover while fighting a wildfire in eastern Nebraska in October 2023. He told his story and talked about his recovery, and advised firefighters on how best to avoid a situation like the one he experienced. Also at the Monday evening program, a video about Loess Hills Cooperative Burn Week premiered. The video was created by Amanda Trudell and Shelly Eisenhauer at the 2022 Burn Week. Most of the rest of the week included boots-on-the-ground, live action training with prescribed fire. Participants were divided into several units to conduct multiple burns at the same time. State and county private lands and some private lands were included, both in the Loess Hills landform and on the Missouri River floodplain. More information, including reports on previous Loess Hills Cooperative Burn Weeks, is available at http://www.loesshillsalliance.com/fire.html

Next year's Burn Week will be held in the northern Loess Hills.

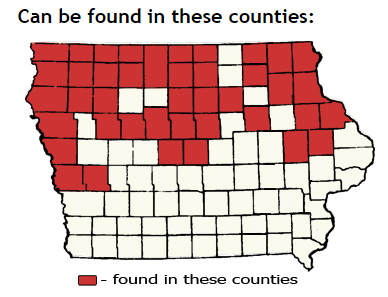

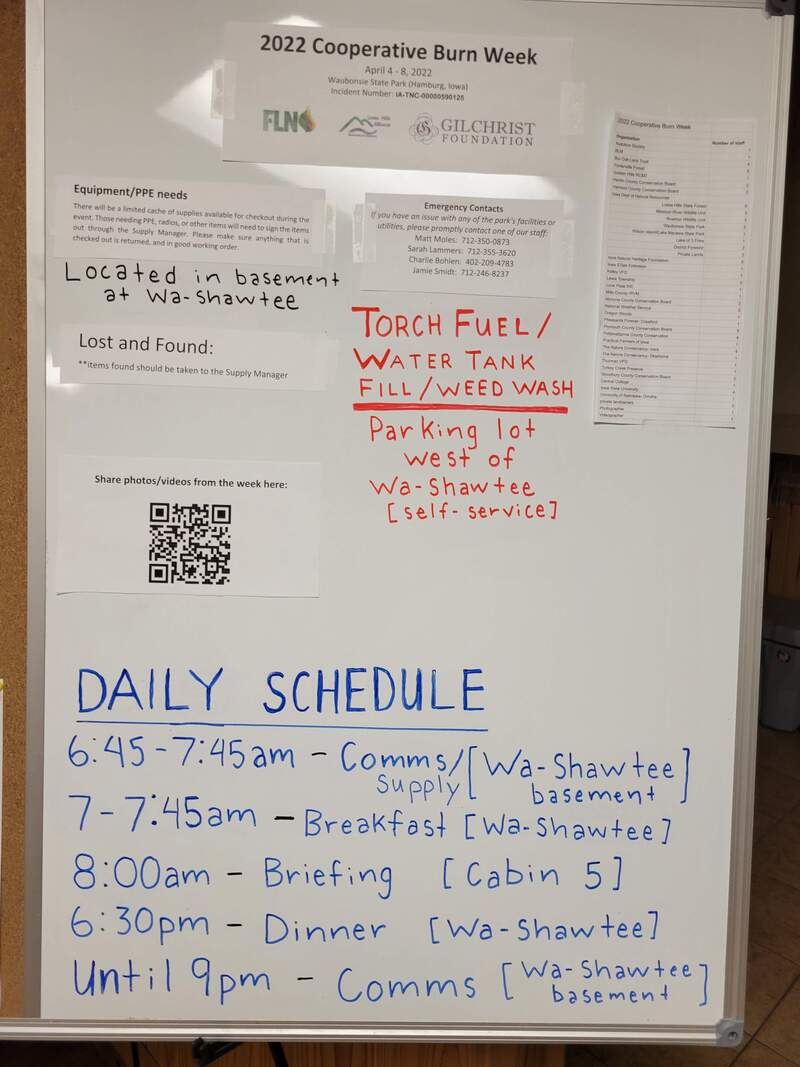

If you'd like to see these little flowers with blue, purple, and sometimes nearly white petals, head to Harrison, Monona, Woodbury, and Plymouth counties on the Loess Hills National Scenic Byway. Brent's Trail and the Pisgah unit of the Loess Hills State Forest are great places to find pasque flowers. Their range also includes Shelby County on the Western Skies Scenic Byway and all counties on the Glacial Trail Scenic Byway (O'Brien, Cherokee, Buena Vista, Clay). Earlier this month was the Loess Hills Cooperative Burn Week, an annual event sponsored by the Loess Hills Fire Partners. Burn Week provides partners with an opportunity to achieve fire management where additional skills and resources are needed to accomplish work at a landscape scale. It is also an opportunity to build relationships with partners, share knowledge and skills, and work within a more complex organizational structure than usual, using the Incident Command System. This year's focus was on the southern Loess Hills and based out of Waubonsie State Park in Fremont County. Nearly 90 participants from nearly 40 organizations participated this year. While weather was not ideal for burning most days, several units were burned on Monday and Tuesday. When conditions did not allow for burning, participants did a variety of trainings and educational sessions both indoors and outdoors. Fortunately several of the partners were able to return to Waubonsie later in April to conduct the planned burn at the park. Learn more about fire in Loess Hills prairies here and here. Check out the photos and videos below to see what this year's burns looked like. updated 2-22-23 The last week of February is Invasive Species Awareness Week, which is "an international event to raise awareness about invasive species, the threat that they pose, and what can be done to prevent their spread." Iowa's landscape has many non-native plant and animals species that can wreak havoc on native plant & wildlife communities, as well as cause economic damage. Invasive species have varying levels of concern depending on their impacts. Some invasive species cause relatively few problems, while others can destroy native ecosystems. Some require action to avoid legal consequences, while others are more a concern to land managers working to restore prairies and savannas. Eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), for example, is one species that can take over and shade out native prairie species, resulting in dense monocultures of coniferous trees where almost no other species can survive. Although they are actually native to the region, removing fire and grazing animals from the landscape has led to their proliferation in recent decades. Smooth brome (Bromus inermis) is a grass that was planted in livestock pastures, along roadsides, on terraces and grassed waterways, and elsewhere across the Midwest. While it's not necessarily a problem in every site, it can be challenging to control in prairie restorations and reconstructions. If you have an area where you'd like to restore or create a prairie, you will need to manage the brome. Crown vetch (Coronilla varia) is a non-native legume that was planted for erosion control and ground cover. It has physical similarities to native vetch species but should be eradicated. Reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea) prefers wetter areas and has resemblance to some native grasses. These species are problematic in prairies and wetlands because they can crowd out native species. In woodlands, garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is one of the most aggressive understory species. Like cedars, it can take over an area and prevent most other species from growing. Tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) was planted as an ornamental and is one of the fastest-growing and -reproducing woody species around. Garlic mustard and tree of heaven can quickly take over a woodland and prevent native species from growing. Some species are listed as noxious weeds and landowners have a legal obligation to remove them. If you have confirmed presence of noxious weeds on your land, you should take action to eradicate them. The links below have full listings of all invasive flora species in Iowa as well as fauna such as insects and aquatic species. If you like the look of certain invasives, plant a native species with similar characteristics instead. Check out the Midwest Invasive Plant Network's Landscape Alternatives for Invasive Plants of the Midwest brochure and mobile app to help find native species. Golden Hills worked with Dr. Tom Rosburg of Drake University on a Common Weeds & Invasive Species virtual program in 2022. View the class recording here or below. Here are several additional resources to learn more about invasive species in Iowa:

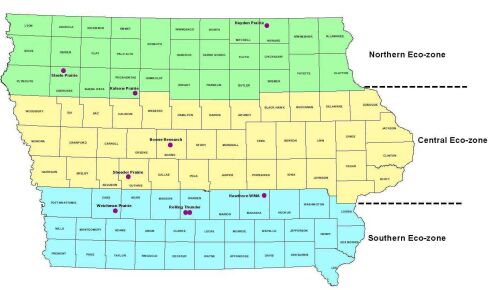

Last week we had the opportunity to visit the Iowa Department of Natural Resources' Prairie Resource Center (PRC). The PRC provides prairie seed to public lands (state wildlife areas and parks) across Iowa. Their operations are primarily located at Brushy Creek State Recreation Area in Webster County, with additional facilities at North Central Correctional Facility in Calhoun County. Staff and volunteers visit remnant prairies in different parts of the state to harvest local ecotype seed. They then clean and store seed, and share it with public land managers within the respective eco-zones. From DNR's PRC website: "A plan was devised to divide the state into 3 zones, the northern 3 tiers of counties, the central 3 tiers of counties and the southern 3 tiers of counties. (This plan is in synchronization with the Iowa Ecotype Project/University of Northern Iowa which works with private seed producers.) For instance, pale purple coneflower is harvested from several prairie remnants in the north zone. Seed is cleaned, grown into 4-6 inch plants in a greenhouse, and planted into a single-species, cultivated row with other plants from northern Iowa. Seed is collected by hand or by use of a small combine and returned to public land in northern Iowa. Native grass seed is collected, planted in larger field situations and harvested with a combine equipped with a unique rice-head stripper. This allows seed to be harvested yet the valuable residue remains as winter cover for a variety of wildlife species." Map of Iowa's eco-zones: Photos of some of the harvested seed to be cleaned: A variety of equipment, both large and small, is used to remove seed from hulls, chaff, and other debris, The leftovers are kept separate and returned to fields to provide nutrients to the prairies. An example of cleaned seed: In addition to seed harvesting and cleaning, the Prairie Resource Center has a greenhouse where they grow native plants. Most of the plants are used in their seed plots. Seed plots provide an easy way to harvest specific species, planted in rows, versus searching through prairies to find one species and harvesting by hand. Due to the scale of operations, the DNR uses tractors and combines for some seed harvest, in addition to hand-harvesting remnant prairies. Below is an example of a seed spreader that is used to sow prairie seed. Golden Hills would like to thank Laura Leben with DNR for providing the tour.

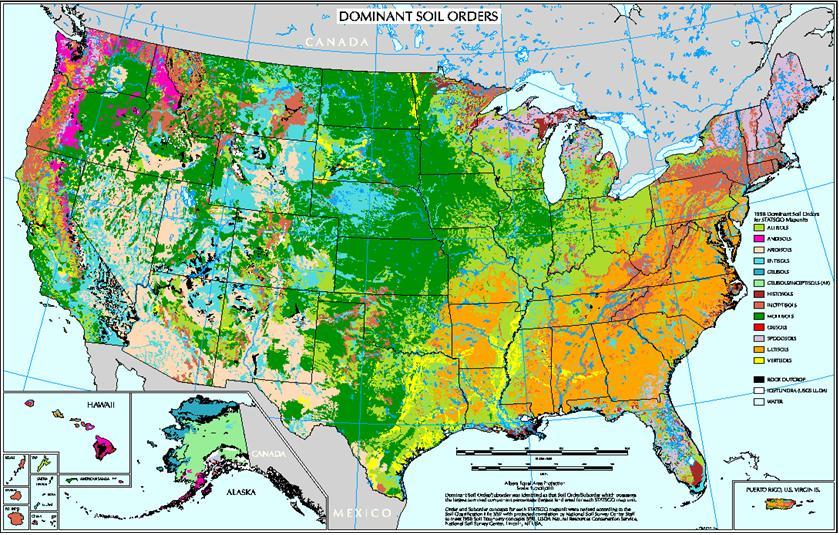

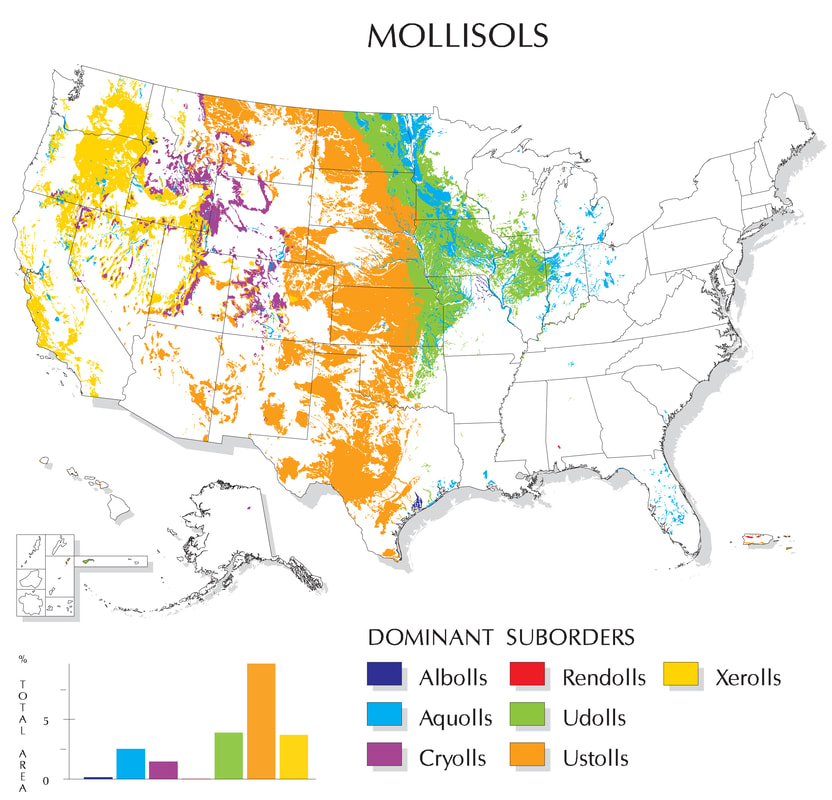

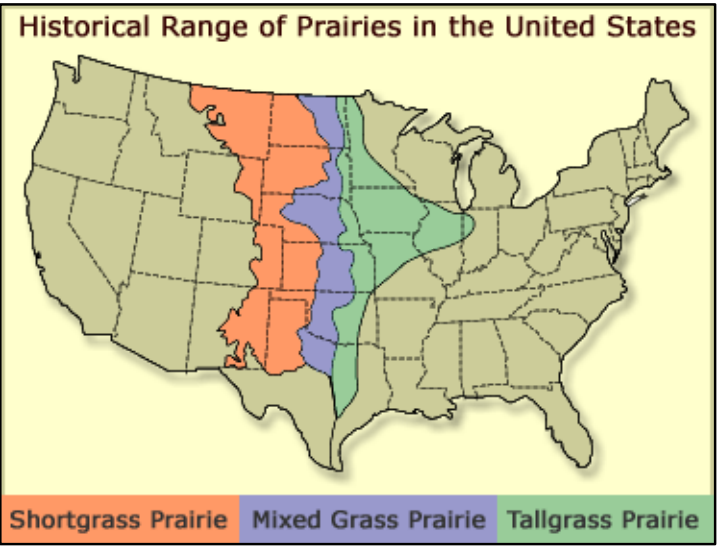

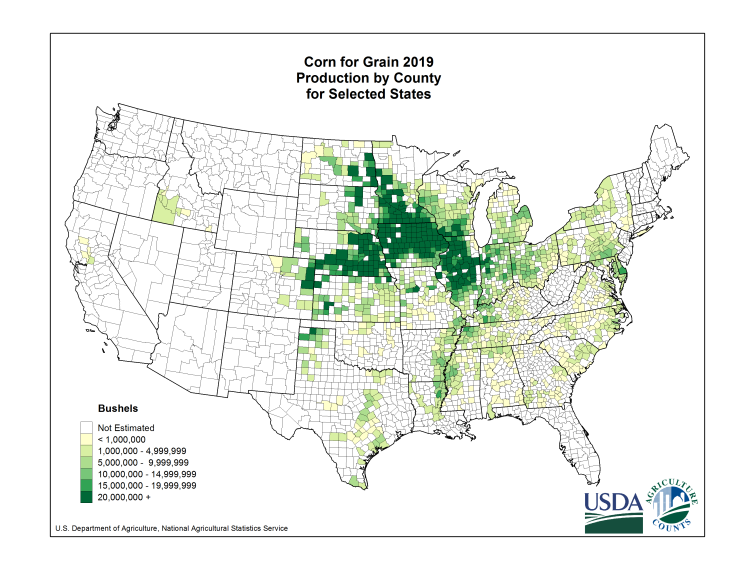

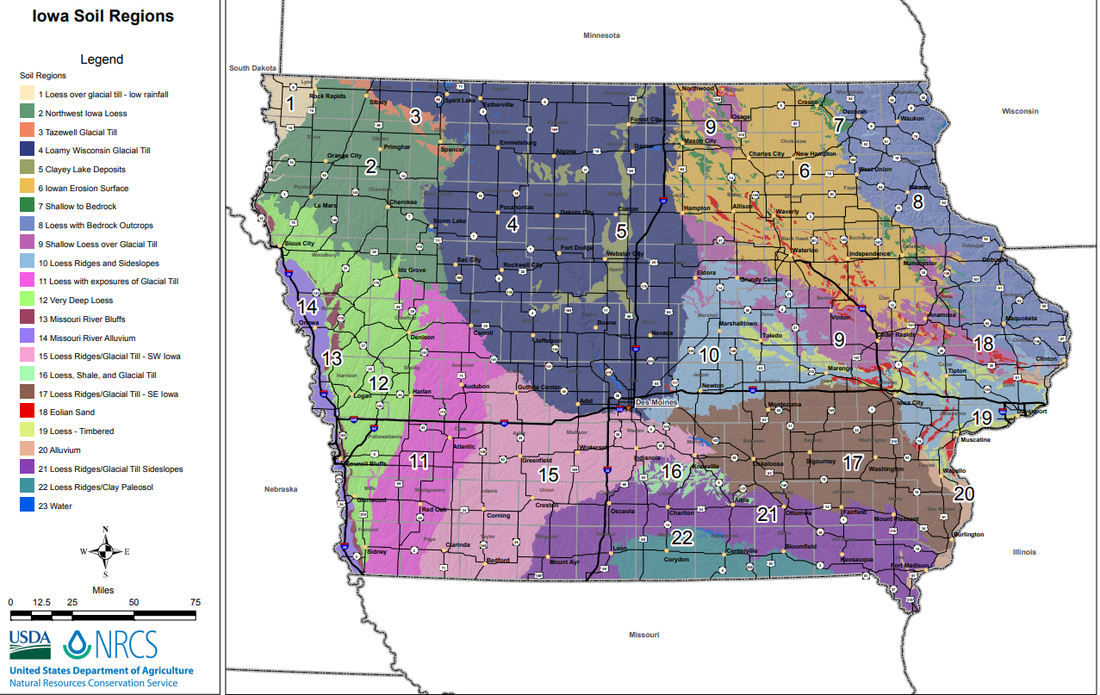

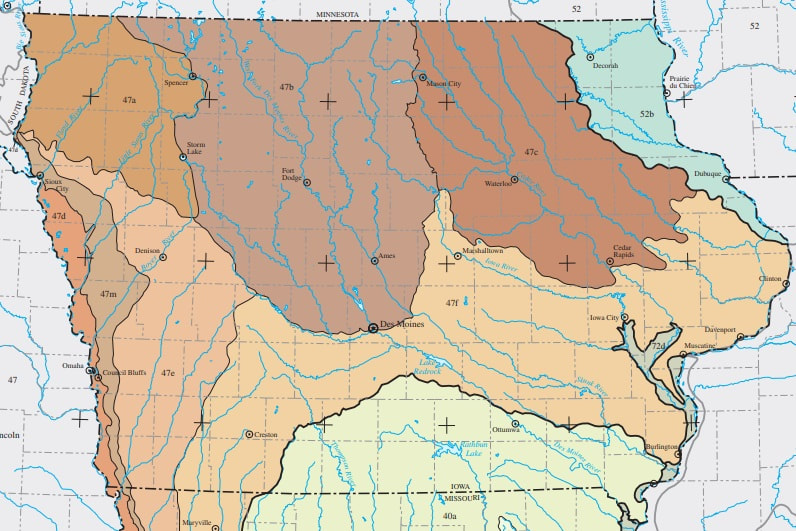

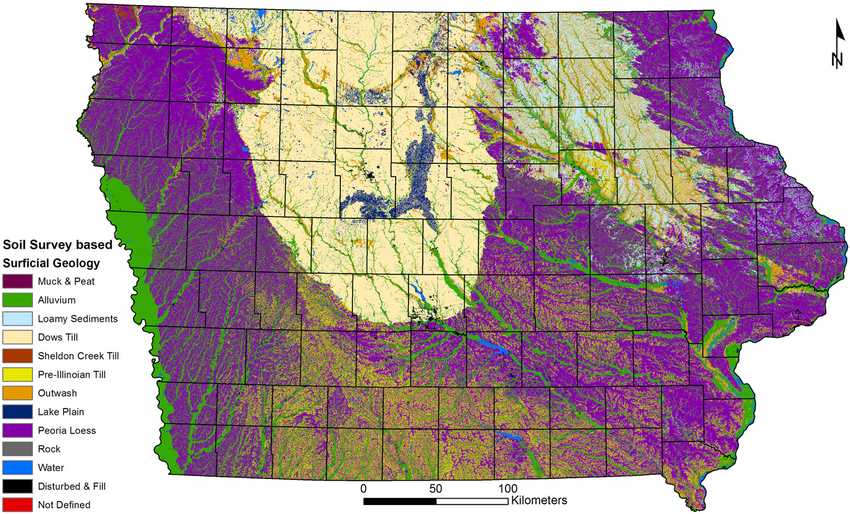

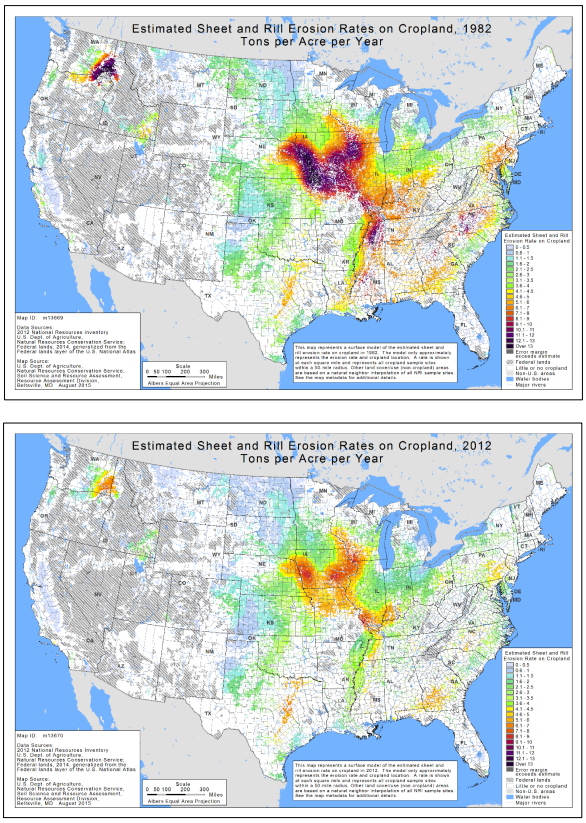

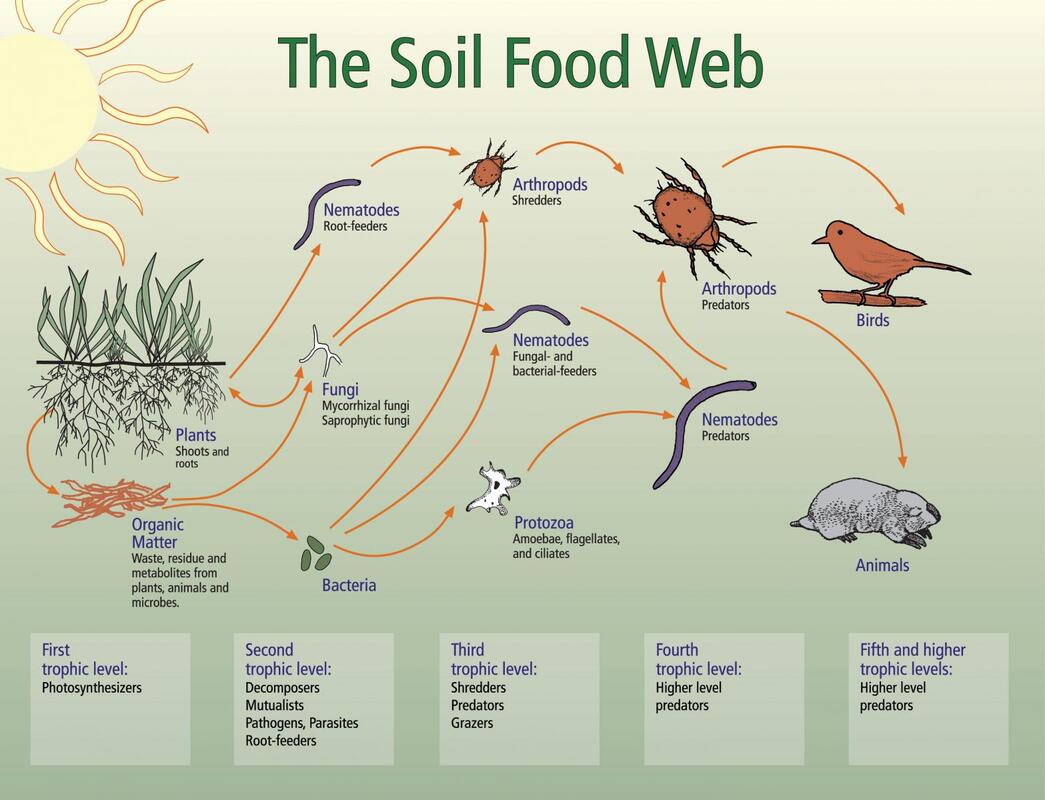

We recently received a Specialty Crop Block Grant entitled Perennial native seed production for rural resilience. With this project, we will be working with public and private landowners to establish native seed production plots. Project updates will be posted at goldenhillsrcd.org/prairieseed. Email [email protected] with any questions about this project or the PRC visit. December 5th is recognized as World Soils Day. Iowa, perhaps more than any other state, owes its agricultural heritage and economy to some of the most fertile topsoil in the world. The dominant soil order across the region is called Mollisols (dark green in the below map). Mollisols are grassland soils that developed over centuries or millennia within prairie ecosystems. Within the order of Mollisols, Udolls (green in the map below) are the predominant suborder: Udolls align closely with the tallgrass prairie region, while Ustolls (another suborder of Mollisols) dominate the mixed- and short-grass prairies: More than 99.9% of Iowa's tallgrass prairies have been destroyed by human development, and largely replaced with corn. Corn is a plant within the grass family, and like the many types of native grasses, it is well-adapted to thrive in the Udoll soils. The former tallgrass prairie is now aligned closely with the Corn Belt: Iowa is divided into several soil regions (map below). In western Iowa, you've probably heard the term "loess" before. Besides the Missouri River Alluvium (14), which is floodplain soil on the flat bottoms of the Muddy Mo, most of the region is covered in a layer of loess. East of the alluvial plain are Missouri River Bluffs (13) and Very Deep Loess (12), which includes the Loess Hills landform. The Loess Hills are typically defined as having at least 60 feet of loess, though many of the bluffs adjacent to the Missouri floodplain are much deeper than that, even up to 200 feet deep. Learn more about the Loess Hills here. Loess was deposited through aeolian processes (wind-driven), with prevailing westerly winds dropping the deepest soils closer to the Missouri River. Moving east, the depth of loess gradually decreases over southern Iowa. The Des Moines lobe was glaciated more recently and lacks this loess. The depth of loess aligns closely with the EPA-designated ecoregions of Iowa. 47d (Missouri Alluvial Plain) is the same as soil region 14 above. Ecoregions 47m (Western Loess Hills) and 47e (Steeply Rolling Loess Prairies) are similar to soil regions 11 & 12. In the map below, purple areas have Peoria Loess, and green areas are alluvial soils. Most of western Iowa is either purple or green. The Des Moines lobe stands out as not having loess deposits. Loess is highly erodible. The maps below from USDA show how the deep loess soils of Iowa, along with the loess region of the Palouse in eastern Washington, have some of the worst soil erosion on the continent. Fortunately, however, conservation practices like terraces and grassed waterways have significantly reduced this erosion over the past 40 years. While many people think of soil as just dirt, there are complex ecosystems living within it. “Essentially, all life depends upon the soil… There can be no life without soil and no soil without life; they have evolved together” - Dr. Charles E Kellogg, Soil Scientist and Chief of the USDA’s Bureau for Chemistry and Soils. Even if you don't farm or garden, the food you eat on a daily basis depends on healthy soils. If soil is treated "like dirt," these webs suffer and soil health declines. Our agricultural economy, waterways, and wildlife also depend on soils to thrive. Historically, poor soil health has contributed to the collapse of entire civilizations. This is why President Franklin Delano Roosevelt said, “The nation that destroys its soil, destroys itself" following the Dust Bowl. Soil health is becoming increasingly important in agricultural discussions and we should not overlook the humble humus beneath our feet.

In September and October, Golden Hills had funding from The Gilchrist Foundation to continue our Prairie Seed Harvest project in the Loess Hills. We also have funding from Pottawattamie Conservation Foundation to do prairie seed harvest at Hitchcock Nature Center specifically. At each event, Project Coordinator Lance Brisbois provided a brief training on identifying species and ripe seed, then showed how to harvest the seed.

Events Summary:

Through these events, we engaged more than nearly 100 volunteers of all ages totaling approximately 187 volunteer hours, worth well over $5,000 of time that would have otherwise been incurred by local conservation agencies with limited time and budgets. The seed we harvested was combined with seed purchased from other sources to be used on prairie restoration projects totaling several hundred acres. All seed collected from state lands was donated to Iowa Department of Natural Resources staff per state regulations. Most seed collected from other areas was given back to local conservation agencies for their prairie restoration efforts. Golden Hills saved a small amount of seed (with written permission) from land owned by county conservation boards for native plant propagation in partnership with Iowa Western Community College. We will grow some of this seed in their greenhouse over the winter and host a native plant sale in spring 2022. Some of the seed has also been saved by Golden Hills to start a small native seed bank. This seed will be stored long-term and added to each year, with the intent of growing a seed bank of local ecotype native species. We thank all the volunteers who helped this year, and look forward to hosting more seed harvest events in 2022. Thank you to The Gilchrist Foundation and Pottawattamie Conservation Foundation for their financial support. As part of this year's Giving Tuesday (November 30), we have a goal of 40 donors and $4,000 to support our Prairie Seed Harvest project. Learn more and donate here. Broken Kettle Grasslands, owned and managed by The Nature Conservancy (TNC) in Iowa, recently held their annual bison roundup. Partners and volunteers from throughout the region helped round the bison up to check the health of the animals, weight them, and vaccinate them before releasing them back onto the prairie. Bison were, for thousands of years, an integral component of prairie ecosystems. TNC reintroduced bison to help control invasive species and improve prairie habitat. Broken Kettle, north of Sioux City along Loess Hills National Scenic Byway in Plymouth County, includes the largest remnant prairie and largest roadless area in Iowa. This area is the only known site with a population of prairie rattlesnakes in the state. The bison at Broken Kettle came from Wind Cave National Park and are called genetically pure since they have no cattle ancestry like most other bison found in the country today. The herd totals more than 200 and they spend the rest of the year roaming approximately 1,900 of the preserve’s 3,000 acres.

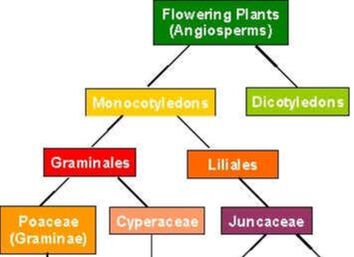

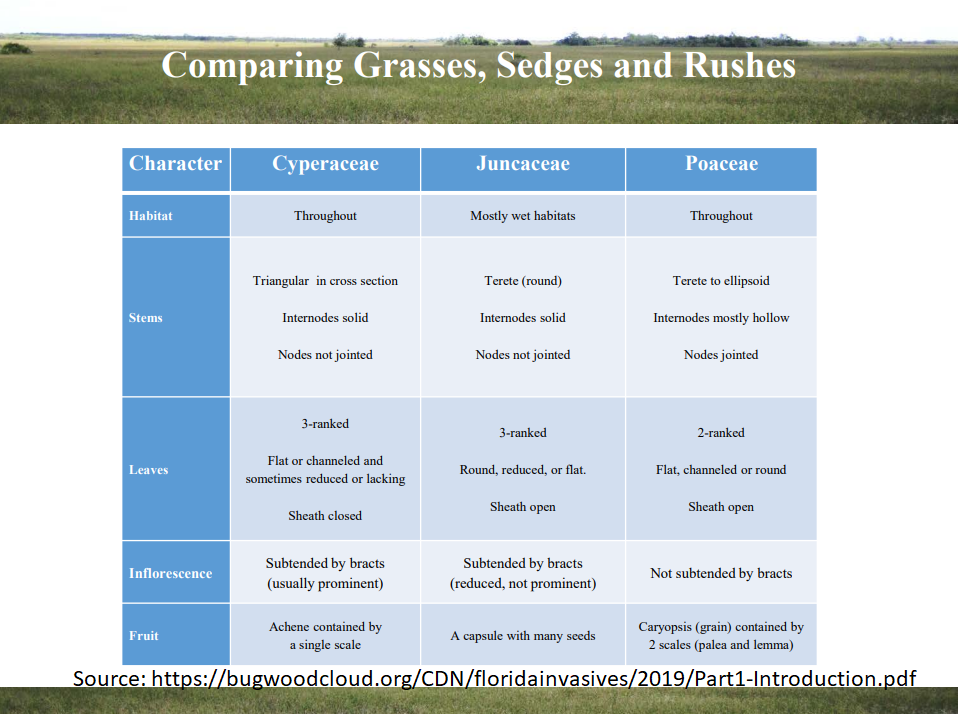

"Sedges have edges

Rushes are round Grasses have nodes that are easily found (or 'grasses are hollow, what have you found?')" If you've done much plant identification, you may have heard this or a similar expression. Prairies, in short, are grasslands. They are dominated by grasses and grass-like plants such as sedges and rushes, along with abundant forbs (flowers) but only sparse woody vegetation (trees & shrubs). At first glance, especially from a distance, prairies may look like monotonous monocultures. This could not be farther from the truth. A high-quality tallgrass prairie remnant can have more than 300 species, many of which are grasses, or grass-like plants. In our Loess Hills Plant List, which includes many of the species found in western Iowa's natural areas, we have identified 58 species in the Poaceae family, 35 in Cyperaceae, and 4 Juncaceae. In other words, grasses are the most common, followed by sedges and rushes. Overall, there is greater species diversity of forbs (flowering plants), but typically the quantity of grass and grass-like plants exceeds that of forbs in prairies.

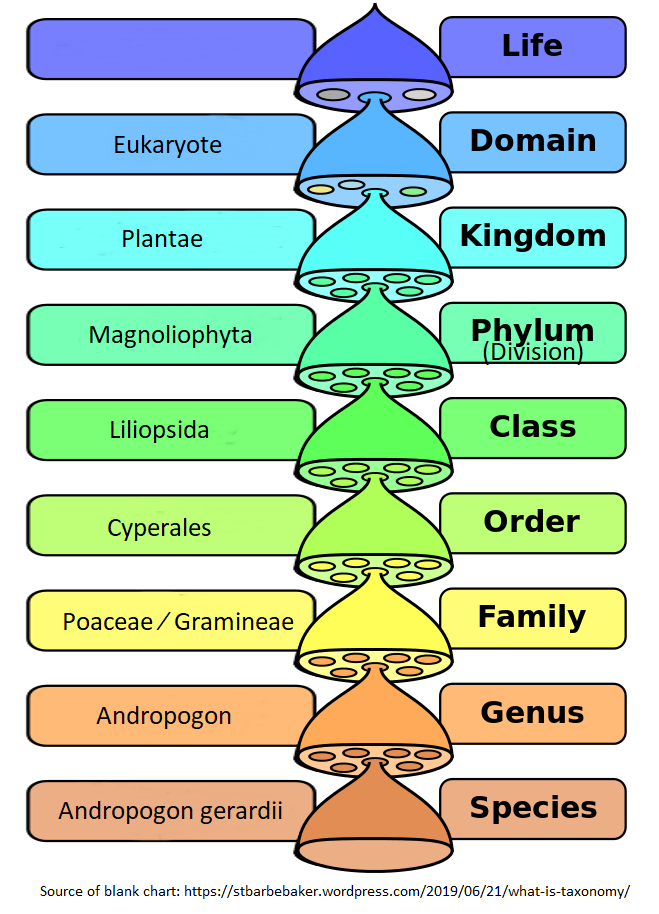

Grasses, sedges, and rushes are all monocots. Monocots have one seed leaf and share other common characteristics. "Although all grass-like plants are monocots, not all monocots are grass-like plants." Learn more in this short video from Native Plant Trust:

Differences between the three can include stem structure, sheath form, and flower type, This page from Minnesota Wildflowers is an excellent synopsis of the differences. The chart below from Florida also provides a great summary.

Grasses are commonly sorted into warm-season and cool-season species. According to Missouri Prairie Journal: "Native cool-season grasses are referred to as “C3 grasses” because, during photosynthesis, they use the Calvin-Benson cycle and produce three carbon molecules, while a C4 grass does not directly use the Calvin-Benson Cycle and produces a four-carbon molecule...

These physiological differences allow native cool-season grasses to grow and reproduce in cooler conditions, offering forage in early spring, fall, and part of winter, and seed by early summer, while warm-season grasses continue growing when cool-season grasses are dormant. For more information on comparing these two groups of grasses" (Read more here).

Warm-season grasses include some of the most common grasses in many prairies, such as andropogon gerardii (big bluestem), schizachyrium scoparium (little bluestem), sorghastrum nutans (Indian grass), panicum virgatum (switchgrass), and bouteloua curtipendula (side-oats grama).

Native cool-season grasses include elymus canadensis (Canada wild rye), elymus virginicus (Virginia wild rye), and koeleria macrantha (June grass). Many non-native pasture grasses, such as brome and fescue, were planted because they can provide a food source for plants earlier in the season compared to many of the native warm-season grasses.

Sedges, in the family Carex, are the next most abundant grass-like plants in Iowa's prairies. This blog post by Leland Searles also offers helpful information: "Sedges are an important, often overlooked group of native plants. In Iowa there are at least 125 species belonging to one genus, Carex."

People often remember "sedges have edges" to help identify them while in the field using their stems.

Golden Hills worked with Dr. Tom Rosburg to record this Carex Identification class in March 2021. Dr. Rosburg covers some of the more common sedges found in Iowa. A sedge identification key and other resources can be found at goldenhillsrcd.org/plantid.

Dr. Anton Reznicek (Curator of the University of Michigan Herbarium and Research Scientist in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology)

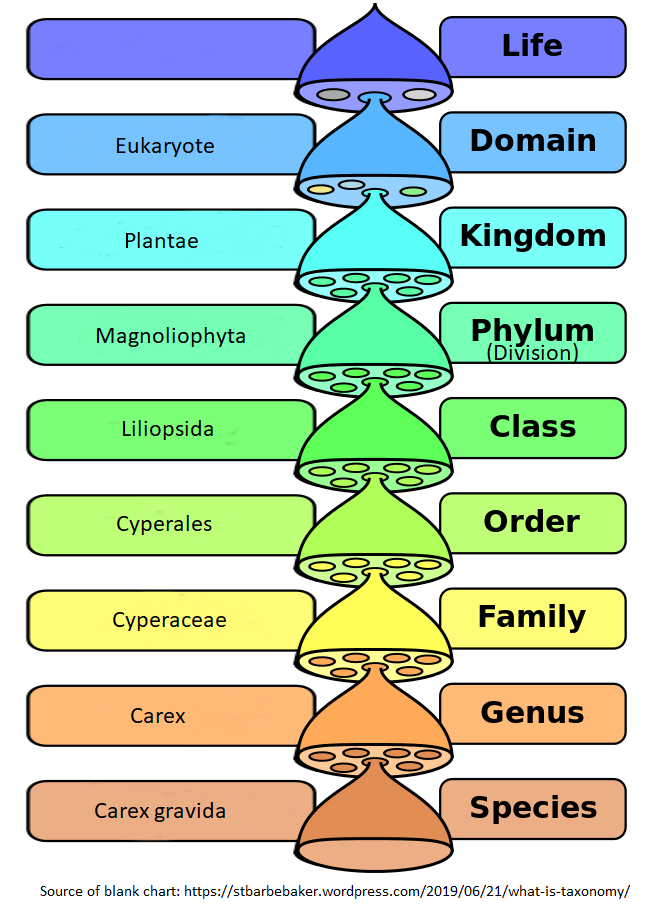

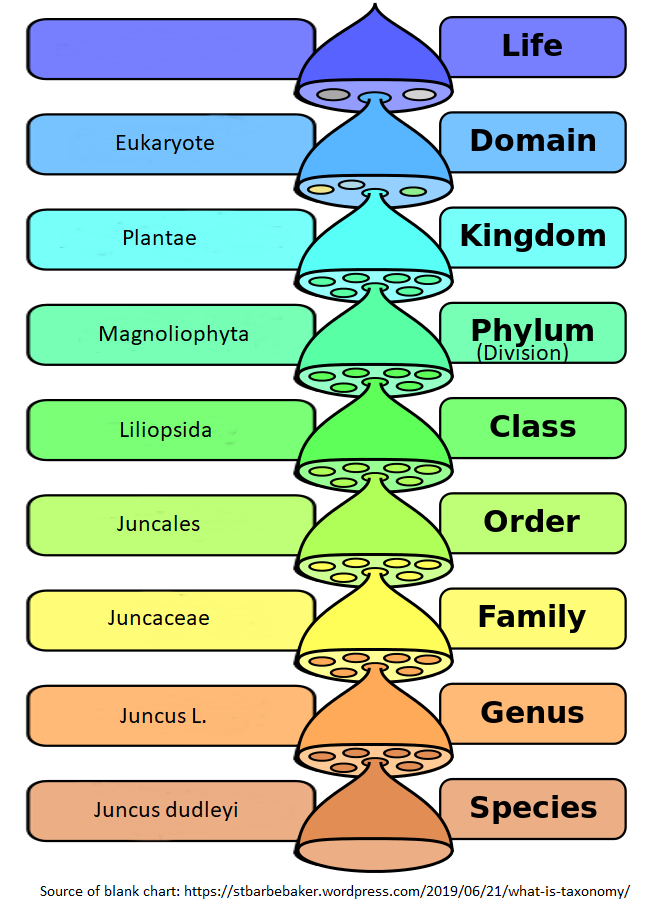

The charts below show how a grass (andropogon gerardii/big bluestem), a sedge (carex gravida/heavy sedge) and a rush (juncus dudleyi) are

In this video, Bob Lichvar of the US Army Corps of Engineers briefly describes how to field-identify common rushes.

The taxonomic charts below show where three common species fit into into the classification system. Andropogon gerardii (big bluestem) is a grass, carex gravida (heavy sedge) is a sedge, and juncus dudleyi (Dudley's rush) is a rush.

As important as it is to learn native plants, it's also good to identify invasive and unwanted plant species that can harm native prairie, wetland, savanna and woodland ecosystems. Reed canary grass is one of the most aggressive invasive grasses. It can take over large areas in short amounts of time and crowd out native species. Removing it once it is establish can be very difficult, so it's better to identify it early and prevent it from spreading as much as possible. The Grasses of Iowa's Weedy and Invasive Grasses page is a great resource for learning about non-native and problematic species.

Links & Resources for grass & grass-like plant ID and classification:

|

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Address712 South Highway Street

P.O. Box 189 Oakland, IA 51560 |

ContactPhone: 712-482-3029

General inquiries: [email protected] Visit our Staff Page for email addresses and office hours. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed