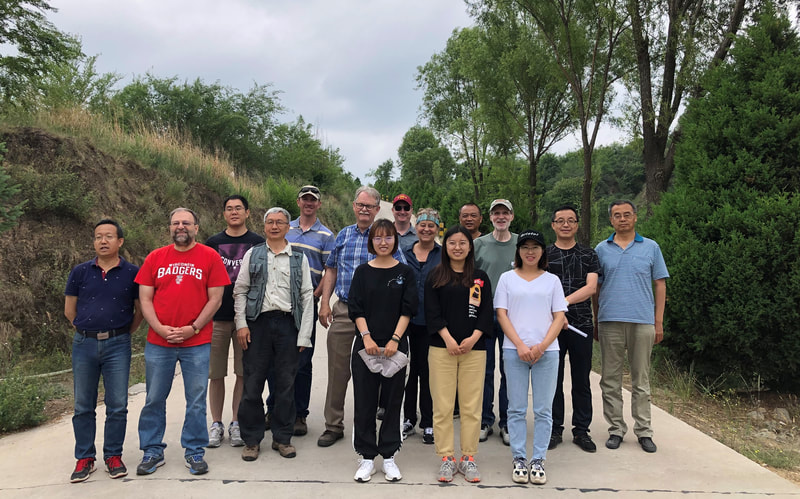

U.S.-China Exchange on Loess Landforms (UCELL)

Yangling city, Shaanxi province

June 18-21, 2019

Click here to read a summary of the 2019 event!

Read the "Loess Country" article series here.

Meeting Site: Institute of Soil and Water Conservation, Northwest Agricultural & Forestry University, No.26 Xinong Road

Off-Site Research Station Locations: Chang Wu (northwest) and Ansai (northeast)

Purposes of Meeting

Click here to view presenter bios.

(Click on the blue underlined text below to download presentations.)

Tuesday, June 18, 2019

Overview of Loess Landforms

Past Restoration Efforts, Techniques, Challenges & Successes—cont’d.

Research on Loess Landforms

a. Research: Soils & Water Issues

b. Research: Soils & Water Issues—continued

Yangling city, Shaanxi province

June 18-21, 2019

Click here to read a summary of the 2019 event!

Read the "Loess Country" article series here.

Meeting Site: Institute of Soil and Water Conservation, Northwest Agricultural & Forestry University, No.26 Xinong Road

Off-Site Research Station Locations: Chang Wu (northwest) and Ansai (northeast)

Purposes of Meeting

- Share background information about the nature and value of the rare deep loess landforms in China and the U.S., including their scope, history, and cultural and economic importance, but especially their geological formation and evolution, soil content and properties, water features and control, erosion, degradation, pollution, biodiversity (fauna and flora—including invasive species), and large and small-scale restoration and protection efforts and techniques.

- Identify the key ecological challenges of those landforms, including the current state of knowledge, results of past and planned research, and ongoing research needs, with a special emphasis on past and possible solutions (including the ecological, social and economic consequences where known).

- Identify opportunities for: (1) new research on loess and the two deep loess landforms, and (2) further U.S.-China collaboration or other exchanges on research and other actions related to the protection of the two landforms.

Click here to view presenter bios.

(Click on the blue underlined text below to download presentations.)

Tuesday, June 18, 2019

Overview of Loess Landforms

- Scope, geological and cultural history and current status; overview of the current condition of the landforms and the threats to them

- Why the preservation/protection of the Loess Landforms (U.S. and China) is important (environmentally/biologically, socially, and economically)

- U.S.:Bill Blackburn/ Graham McGaffin (US Overview) and Zhang Xiaoquan (China Restoration)

- Iowa’s Loess Hills are 640,000-acre mini-mountains (bluffs) in the Midwest U.S. that run parallel to the Missouri River 220 miles from Mound City, MO to Westfield, IA. In Iowa, the beautiful sharp-cliffed hills pass through the western sides of Fremont, Mills, Pottawattamie, Harrison, Monroe, Woodbury, and Plymouth Counties. They are geologically speaking relatively new, having been formed only 12,000 t0 115,000 years ago when glaciers were grinding rock into powder in the north, which was carried down the Missouri River, deposited on the bottom ground and eventually blown westerly into dunes. This landform is significant for local wildlife, economics and culture. While considerable areas of the Hills have been restored and protected, there are still issues (erosion, invasive species, soil mining, certain land development) that threaten them. The presentation lays out shared priorities for conservation.

The Nature Conservancy in China has been focused on a number of restoration projects in the China Loess Plateau that have used state-of-art practices.

- Iowa’s Loess Hills are 640,000-acre mini-mountains (bluffs) in the Midwest U.S. that run parallel to the Missouri River 220 miles from Mound City, MO to Westfield, IA. In Iowa, the beautiful sharp-cliffed hills pass through the western sides of Fremont, Mills, Pottawattamie, Harrison, Monroe, Woodbury, and Plymouth Counties. They are geologically speaking relatively new, having been formed only 12,000 t0 115,000 years ago when glaciers were grinding rock into powder in the north, which was carried down the Missouri River, deposited on the bottom ground and eventually blown westerly into dunes. This landform is significant for local wildlife, economics and culture. While considerable areas of the Hills have been restored and protected, there are still issues (erosion, invasive species, soil mining, certain land development) that threaten them. The presentation lays out shared priorities for conservation.

- China: Zhou Jinfeng

- John Liu

- Located in the north-central part of China, the Loess Plateau is one of the four plateaus of China. It is one of the cradles of ancient Chinese civilization. It is also the most concentrated, highest, and largest loess area on the earth. It covers a total area of 640,000 square kilometers and spans most or part of China's Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Shanxi and Henan provinces. Centuries ago it was degraded from grazing and other agricultural practices, resulting in severe erosion to the Yellow River basin, where the deposits made flooding worse. In recent decades, a concentrated effort was made through the World Bank and Chinese government to recruit farmers and other local peoples to successfully restore large tracts of the Plateau through terracing, planting vegetation and revised agricultural practices.

- Located in the north-central part of China, the Loess Plateau is one of the four plateaus of China. It is one of the cradles of ancient Chinese civilization. It is also the most concentrated, highest, and largest loess area on the earth. It covers a total area of 640,000 square kilometers and spans most or part of China's Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Shanxi and Henan provinces. Centuries ago it was degraded from grazing and other agricultural practices, resulting in severe erosion to the Yellow River basin, where the deposits made flooding worse. In recent decades, a concentrated effort was made through the World Bank and Chinese government to recruit farmers and other local peoples to successfully restore large tracts of the Plateau through terracing, planting vegetation and revised agricultural practices.

- John Liu

- a. Restoration Projects Overview

- U.S.: Graham McGaffin (with Zhang Xiaoquan-China) / Bill Blackburn

- The presentation examined the elements of small area restoration typically used in the Iowa Loess Hills and some of the current practices being used on a larger scale, particularly prescribed fire. It described the importance of Loess Hills conservation and restoration for larger regional and North American environmental priorities (e.g. water quality, North American tallgrass prairie conservation, etc.).

- China: Zhou Jinfeng

- U.S.: Graham McGaffin (with Zhang Xiaoquan-China) / Bill Blackburn

- b. Erosion issues and research

- China: Baoyuan Liu

- U.S.: John Thomas

- The Hungry Canyons Alliance was formed locally to research and implement solutions to the problem of stream channel degradation in a 19-county area of the deep loess soils region of western Iowa. Channelization of streams and land-use changes during the first half of the 1900s caused stream channels to erode resulting in widespread damage to public and private infrastructure (bridges, culverts, utility lines, etc.), loss of farmland, and increased sediment loads. A proven, affordable solution is to build grade-control structures (GCS) in streams which promote stream stability by allowing the stream elevation to drop in a controlled setting, restoring lost stream grade, preventing further downcutting, decreasing sediment loads, and increasing water quality. With more than 2,000 large GCS in an area of approximately 20,000 square kilometers, western Iowa has the highest known concentration of GCS anywhere in the world. The Hungry Canyons Alliance has also pioneered the use of directional drilling to control deep gully headcuts in small watersheds and has experimented with new bank stabilization techniques and materials.

Past Restoration Efforts, Techniques, Challenges & Successes—cont’d.

- Plant & water issues and research

- U.S.: Tom Bragg & Barbi Hayes (plants)

- The Loess Hills of the United States and the Loess Plateau of China have a similar geologic base but differ in many ways, in particular having different histories of land use by humans – an ancient history of land use in China and a much shorter history of land use in the U.S. This history, the impact of extended human use on the land form, and the resource demands of today explain some of the reasons for differences in objectives for these two loess-based regions. In the U.S., the persistence of native, albeit remnant, native plant communities provides a gene pool of species adapted to the region that are, thus, ideally suited for ecosystem restoration efforts. Restoration of the Loess Hills to conditions reminiscent of the pre-European landscape is the objective of many if not most of the conservation-based efforts in the Iowa Loess Hills. Historically, the Loess Hills were grass-covered with the occasional occurrence of widely spaced trees, mostly bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa). Maintained by fires of either natural (lightning) or Native American ignition, the Loess Hill prairies of the early 1800's were the exclusive domain of the prairie. With European settlement, however, fires were suppressed and cropland expanded particularly throughout lowlands of most of the Loess Hills area. The hills surrounding these flat lowlands, however, were generally left unmanaged except for some tree felling, mostly for construction material and fire wood. Over time, even in the hilly terrain, further loss of the historic prairie occurred due to development, such as farm houses and structures, and farming of some marginal uplands. The principal cause of the loss of prairie, however, resulted from the natural process of tree succession in the absence of fire such that, by the end of the 20th Century, native trees and shrubs, expanding from fire-refugia in lowlands and ravines, had extensively replaced the prairie in the hills leaving mostly small, disconnected areas of prairie amidst a sea of forest. Efforts in the late 1900's were made to protect some of these remnant areas by establishing nature preserves but protection alone was found not to be an adequate defense against continued loss of prairie habitat. Instead, active management, including prescribed fire and herbicide application of both native and non-native woody and herbaceous species, has been required to maintain these enclaves of our natural history. Research and monitoring today includes studies designed to assess both (1) the effectiveness of ongoing management on prairie plant community species composition and productivity and (2) how, in the absence of continued active management, future ecological succession may change todays vegetation of the Loess Hills.

- China: Li Wang (water)

- U.S.: Tom Bragg & Barbi Hayes (plants)

Research on Loess Landforms

- Overview of key past and current research on loess soils and restoration, and ongoing research needs.

a. Research: Soils & Water Issues

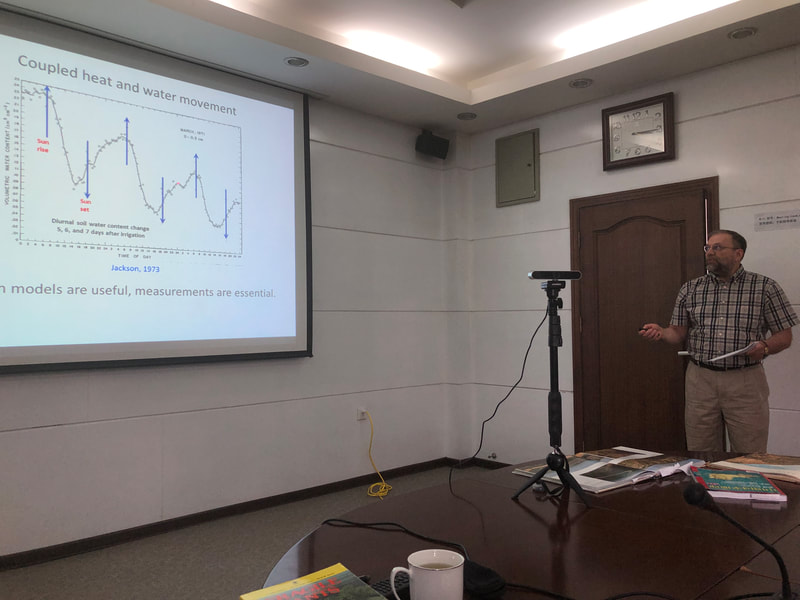

- Sensor Measurement (first half): Bob Horton

b. Research: Soils & Water Issues—continued

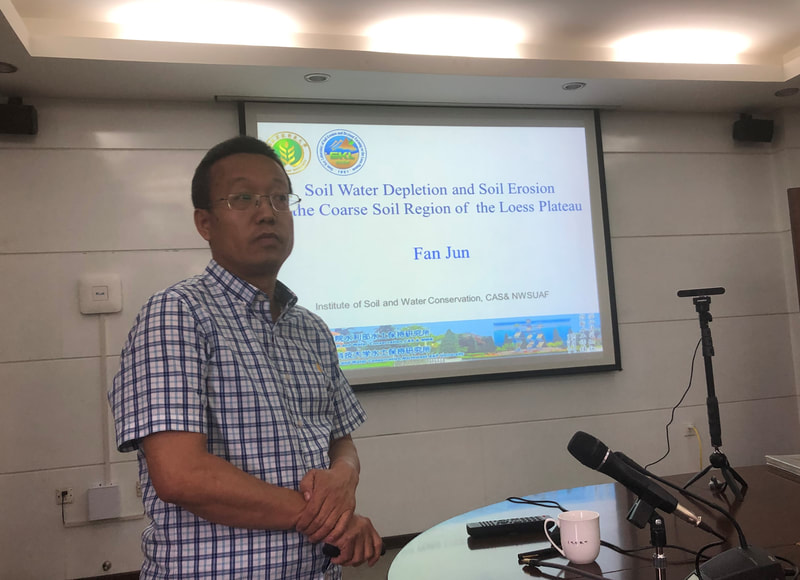

- Sensor Measurement—cont’d. (second half.): Bob Horton, Fan Jun

- Spatial Soil & Water Properties, Loess Geography: Xiaoxu Jia

- Bradley Miller

- The Iowa Loess Hills is the thickest of the loess covering the central United States. However, the extent of loess is larger than most people realize. Loess was generated by the Missouri, Mississippi, Illinois, Wabash, and Ohio Rivers as they were outwash channels from continental glaciers. Through different glacial periods there were multiple events of loess deposition, the largest of which deposited what is called Peoria Loess. This loess formation is 20 m thick within 3 km of the Missouri River valley. The Peoria loess sheet thins and has finer particle sizes in a gradient across Iowa. As a result, much of Iowa has soil textures ideal for crop growth. With the goal of improving the spatial detail of maps showing the distribution of particle sizes in Iowa, the Geospatial Laboratory for Soil Informatics constructed a spatial model. The model was built using machine learning and trained on 2,700 samples from the National Cooperative Soil Survey. Important to this model were distances east from smaller rivers, such as the Nishna Botna and Des Moines Rivers, suggesting that there were also more local contributions of sediment in the Peoria Loess sheet. The model also recognized a pattern of high sand content at the top of the Iowa Loess Hills, grading to finer particle sizes with elevation. This pattern could be due to the original constructional processes of these hills or could indicate severe erosion. There is opportunity to study the finer details of these loess landscapes, both in terms of formation and erosion.

- Soil Properties, Health and Management: Jiangbo Qiao

Photo Gallery

Address712 South Highway Street

P.O. Box 189 Oakland, IA 51560 |

ContactPhone: 712-482-3029

General inquiries: [email protected] Visit our Staff Page for email addresses and office hours. |